Prehistory of the Andean Peoples

© 1998 by James Q. Jacobs

Several times during Andean prehistory

people coalesced into large political entities. It is therefore possible

to consider an Andean civilization and tradition. One indicator of this

social and political unity is Quechua, presently spoken by some 10 million

people from Ecuador to Argentina, a distance of thousands of miles.

Quechua refers to the mountain zone between 3,000 and 11,000 feet in

the Andes of South America. Only in historic times has the term been

applied to Runa Simi, the language of the Inca civilization.

Most of the descendants of the Indians of the Incan realm are the present-day

Aymara and Quechua speaking peoples of the Andes. Quechua speakers constitute

almost half the population of Perú. Aymara and Quechua traditions

are very similar and were unified under the Incas and possibly under

previous political centers, particularly Tiwanaku.

PREHISTORY OF THE ANDEAN PEOPLES

The Andean region produced a unique emergence of civilizations

at an early date. A pre-agrarian, pre-ceramic adaptation to rich, easily

accessible maritime resources coupled with a vertical adaptation to

nearby stacked mountain resource zones enabled very early sedentary

communities to develop along the Pacific coast. Populations grew to

1,000 to 3,000 person villages and large monumental

architecture developed. Contemporaneous to the construction of pyramids

in Egypt and ziggurats in Mesopotamia, Peruvian coastal communities

cyclically renovated ever larger pyramidal platform mounds. Aspero,

a large early center with platform mounds, has 4800 to 5000 BP. carbon

14 dates from late phase construction.

Cultigens are first known in South America from 10,000

BP. Coastal agriculture included introduced cultigens from both the

highland and Amazon zones. A two hundred kilometer transect of the Andes

includes twenty of the world's thirty four life zones in a transition

from extreme aridity to extreme altitude and then extreme humidity and

rainfall. Interaction, exchange and multiple zone exploitation of this

diverse region was facilitated by the beast of burden adaptation of

the llama. During the Pre-ceramic Period (5000 - 4000 BP.) cultivated

squash and tubers introduced from the highlands, tropical tubers, beans

and peppers from the Amazon and a variety of local wild grasses, seeds

and fruits were exploited. By 4,000 BP. irrigation agriculture appeared

in coastal valleys. Cultigens are first known in South America from 10,000

BP. Coastal agriculture included introduced cultigens from both the

highland and Amazon zones. A two hundred kilometer transect of the Andes

includes twenty of the world's thirty four life zones in a transition

from extreme aridity to extreme altitude and then extreme humidity and

rainfall. Interaction, exchange and multiple zone exploitation of this

diverse region was facilitated by the beast of burden adaptation of

the llama. During the Pre-ceramic Period (5000 - 4000 BP.) cultivated

squash and tubers introduced from the highlands, tropical tubers, beans

and peppers from the Amazon and a variety of local wild grasses, seeds

and fruits were exploited. By 4,000 BP. irrigation agriculture appeared

in coastal valleys.

Coastal-Andean interaction spheres are especially evidenced

during the 4000 - 2800 BP. Initial Period, when more mound building occurred

than during any other period. Initial Period centers share a characteristic

U-shaped site layout and mountain facing orientation. Sechin Alto grew

to be the largest. In 3400 BP. Sechin Alto's 300 m. by 250 m. by 40 m.

high colossal, stone-faced mound was the largest American monument. Coastal-Andean interaction spheres are especially evidenced

during the 4000 - 2800 BP. Initial Period, when more mound building occurred

than during any other period. Initial Period centers share a characteristic

U-shaped site layout and mountain facing orientation. Sechin Alto grew

to be the largest. In 3400 BP. Sechin Alto's 300 m. by 250 m. by 40 m.

high colossal, stone-faced mound was the largest American monument.

Chavín de Huantar is

erroneously viewed as the first South American civilization horizon and

coincides with the Early Horizon (2800-2200 BP.). Chavín, located

on a principal pass from coast to jungle, is a monumental site with finely

carved stone sculpture with elaborate iconography and art. The homogeneous

Chavín style followed a diverse heterogeneous pattern in Initial

Period ceramics. At Chavín the monumental architecture includes

a U-shaped principal mound oriented to face the rising sun. Deep within

the platform mound a cruciform chamber is centered on El Lanzón,

a thirteen foot tall, prism-shaped stela that extends from floor to

ceiling. Carved in bas-relief, the stela depiction includes a standing

anthropomorph that combines feline characteristics and serpent depiction.

Around 2250 BP., military architecture appears, coincidental to an

apparent disruption of regional integration.

A second significant South American center emerged in

the southern uplands at Tiwanaku on Lake

Titicaca. The immense lake's 12,600 feet above sea level shoreline supported

a dense population. The Tiwanaku survival strategy augmented the Andean

agropastoral adaptation with a combined raised-bed and shoreline canal

agriculture system. The water temperature in the canals mediated frosts,

effectively extending the short, high-elevation growing season and increasing

yields.

Tiwanaku culture became the largest Andean regional

integration and enjoyed an unprecedented longevity of 1400 years. The

Tiwanaku polity covered large portions of Bolivia, Argentina, Chilé,

and Perú. At Tiwanaku one of the great Andean platform complexes

and one of the highest urban centers ever, was built around 2400 BP.

It grew to house from 25,000 to 40,000 people.

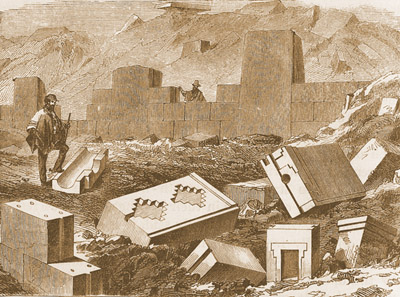

Tiwanaku's central monument precinct covers twenty hectares

and is laid out on a cardinal direction oriented grid. The enormous

Akapana mound is 200 meters long per side and stands 15 meters tall.

Its andesite facing was quarried at 100 kilometers distance. Many of

the major buildings date from the Early Intermediate period (AD 200-600).

During the Middle Horizon (AD 600-1000) Tiwanaku influences are seen

throughout the central and southern Andes. Tiwanaku declined around

1000 BP. Abandonment of the raised bed-canal agriculture system, due

to a natural lowering of the Altiplano's rainfall and the consequent

lowering of the basin's great lake may have contributed to the decline

of the great city.

Moche civilization became a regional integration of

part of the northern Andes contemporaneous with Tiwanaku. The Moche

constructed the largest Andean adobe structure, the Huaca del Sol, one

of the two or three largest South American monuments. The Moche were

followed by the Chimor. They consolidated 1000 km of coast under the

second largest prehistoric polity in South America. Numerous other regional

polities have played a role in the development of Andean civilization.

Local hegemonies, some coastal, some montane and still others bridging

geographic barriers, had risen, expanded, and collapsed prior to the

Incan regional unification.

The greatest of all central polities of the Andes, the

Incan civilization, unified the Andes a mere century before European

intrusion. The Inca state was called Tahuantinsuyu, the 'Land of the

Four Quarters,' and was centered on Cuzco, Perú. Inca was a title

bestowed on the political leader and referred to the ruling ayllu (kinship

group). Today Inca refers both to the people and the polity. The first

Inca, Manco Capac, was revered as a civilizing hero. According to Garcilaso

de la Vega's version of Andean history, Manco Capac came from the Lake

Titicaca region. Felipe Gauman Poma de Ayala wrote that the first Incas

came from Lake Titicaca and Tiwanaku, lived in Tambotoco (also called

Pacaritambo) and four brothers and four sisters left to found Cuzco.

These included Manco Capac and his wife. The greatest of all central polities of the Andes, the

Incan civilization, unified the Andes a mere century before European

intrusion. The Inca state was called Tahuantinsuyu, the 'Land of the

Four Quarters,' and was centered on Cuzco, Perú. Inca was a title

bestowed on the political leader and referred to the ruling ayllu (kinship

group). Today Inca refers both to the people and the polity. The first

Inca, Manco Capac, was revered as a civilizing hero. According to Garcilaso

de la Vega's version of Andean history, Manco Capac came from the Lake

Titicaca region. Felipe Gauman Poma de Ayala wrote that the first Incas

came from Lake Titicaca and Tiwanaku, lived in Tambotoco (also called

Pacaritambo) and four brothers and four sisters left to found Cuzco.

These included Manco Capac and his wife.

Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, the ninth Inca, is considered

the greatest Inca. Around 1438 Pachacuti replaced his brother Inca Urcon

after overcoming the Chanca invasion. Pachacuti consolidated a large

polity, a territory spanning from the Titicaca Basin to central Perú.

Pachacuti is credited with the construction of many monumental sites

and with instituting wise laws. He reconstructed Cuzco, built the Coricancha,

the so-called "Temple of the Sun," and initiated construction of Saxsayhuaman.

Saxsayhuaman's polygonal masonry terraces include many immense stones.

The largest, a twenty-eight feet tall stone has been liberally estimated

to weigh over 360 metric tons (conservatively at 120), one of the largest

stone blocks ever incorporated in a structure.

In 1471 Pachacuti was succeeded by his son Topa Yupanqui.

Topa Yupanqui added Ecuador and northern Perú to Tahuantinsuyu.

In a few generations the Incas consolidated under one government the

Andean region from the border of Colombia to the Rio Maule in Chilé,

nearly 400,000 square miles, potentially the largest nation on the earth

at the time. This area twice the size of Spain encompassed at least

12,000,000 people who spoke more than 20 languages. More than 100 independent

ethnic groups had been consolidated into the Tahuantinsuyu state. Two

great north-south roads, one running along the coast for about 3,600

km, the other inland along the spine of the Andes spanning a comparable

distance, and many interconnecting links helped unify the realm. The

30,000 to 40,000 km of major roadways was one of the best in the world.

A system of runners facilitated communications.

Most of the pre-Colombian population lived above 10,000

feet. The prehistoric economy was based on agriculture, its staples

being corn (maize), potatoes and sweet

potatoes, squash, tomatoes, peanuts (groundnuts), chili peppers, coca,

cassava, and cotton. Some forty domesticated plants were cultivated.

About 700 variety of potatoes are known. They raised guinea pigs, ducks,

llamas, alpacas, and dogs. Alpacas

and llamas were domesticated for their fleece. Llamas, the only beast

of burden in all the Americas, served as pack animals. Clothing was

made of llama, alpaca and vicuña

hair and cotton. Houses were of stone or adobe mud. Practically everyone

was a farmer, producing his/her own food and clothing. Communities took

advantage of the mountain environment by utilizing various elevations

and climates. Alpacas grazed the highest terrain where crops could not

survive.

The Andean peoples are traditionally organized in ayllus,

common descent family groups owning land in community. Animals were

grazed on common pastures. Land use was from time to time redistributed

according to family needs. Irrigation systems supported agriculture

where cultivation was otherwise impossible. Terracing converted steep

mountains into fertile flat fields. One of the greatest engineering

feats of humanity in its time was a river diversions in ancient coastal

Perú. Guano from coastal islands was used as fertilizer and guano

producing birds were protected by law. The specialized Andean adaptations

were highly successful and their cultigens have greatly benefited the

modern world.

Before the Spaniards arrived in the Andes smallpox and

other infectious diseases of European origin swept across the Americas.

Two-thirds or more of the population perished before contact, making

conquest all the easier. Topa Yupanqui's successor, Huayno Capac, died

of European diseases a few years before Francisco Pizarro's conquering

band of Spaniards killed his son, Inca Atahualpa. The conquerors first

held Atahualpa for ransom. They received a 20 by 18 feet room filled

to the ceiling with gold in exchange for the Inca's life before killing

him. So began the Historic Period in the Andes.

See Bibliography page

for citations.

Other Andes academic papers:

TUPAC

AMARU, THE

LIFE, TIMES, AND EXECUTION OF

THE LAST INCA

EARLY

MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE OF THE PERUVIAN COAST

CHAVIN

AND THE ORIGINS OF ANDEAN CIVILIZATION

|