Pecos National Historical Park

A short distance east of the numerous art galleries in

modern Santa Fe, New Mexico, on the southern edge of the Sangre de

Christo mountains, prehistoric Native Americans constructed a large

pueblo on a ridge along Glorieta Creek, near the Pecos River confluence.

The park currently preserves several pueblos, the Spanish colonial

church, Spanish settlements, Santa Fe Trail sites, a section of the

Pecos River, and the Civil War battle sites at Glorieta Pass. Camping

is available in the Santa Fe National Forest, north of the park.

From the Visitor Center and Museum, a self-guided trail leads to

the ancient masonry pueblo and the historic adobe ruins of the

Spanish mission and convent. Interpretations on the trail and in

the museum, like at many southwest parks, are bilingual, in Spanish

and English.

|

Visitors can enter two reconstructed kivas along the trail.

One of the kivas is in the convent area.

Pecos was probably one of the largest

pueblos at European contact, when Coronado and his army of

1,200 arrived at then-called Cicuyé in

1540. A Plains Indian living at Pecos,

with tales of gold, lured Coronado's army

to the Great Plains hoping they would die. He was made to pay

for the ruse, sentenced to strangulation by Coronado.

About 60 years later, in 1598, Spaniards returned

to claim the territory of Nuevo Mexico for Crown and Church,

and to settle and built missions among the Puebloan Nations.

A friar was assigned to Pecos because of its size and its importance

in the Puebloan world. Initial relations included brutal attacks

on Native culture, justified as "idol smashing" by

the Colonial Spanish inquisitional midset. |

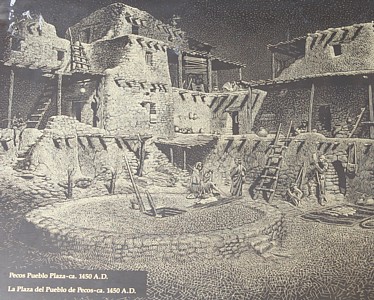

North Pueblo, the major prehistoric feature, enclosed several kivas.

A Spaniard in 1591 reported walls standing to five

stories high, households of 15 or 16 rooms, and neat and thoroughly

whitewashed buildings.

Artful interpertation plaques adorn the visitor trail.

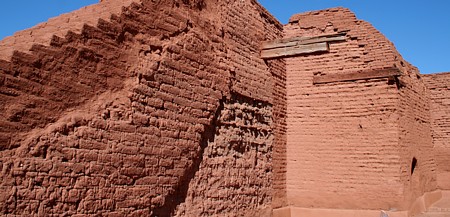

The church ruin standing today was the second church built at Cicuyé.

Both Spanish churches were built on the same spot. Only stone foundation

work of the first survives (below).

Franciscan Friar Andrés

Juárez arrived at Pecos in 1621 and directed construction of the

'Nuestra

Señora de los Angeles de Porciuncula de los Pecos' church,

the largest Spanish colonial structure north of the Mexican border.

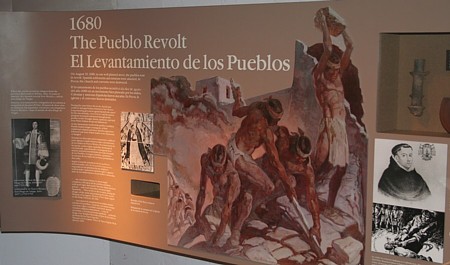

The Natives destroyed the church during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt.

After decades of Spanish control, forced labor, tribute, injustice,

and repression, the Native populations cojoined in a regional revolt, the 1680 Pueblo Revolt,

forcing the Spanish to abandon the entire region north of modern-day

El Paso. Pecos inhabitants killed their priest, destroyed the

massive church, and constructed a once-foridden kiva in the convent

area.

The Spaniards returned with military force after 12 years. Tribute

was abolished as peace was imposed by the sword. The smaller,

rebuilt church was completed in 1717. Native populations

declined, primarily due to diseases—at Pecos from about 2,000

to 300. When the Santa Fe Trail arrived in 1821, a few survivors remained,

then, in 1838, moved to join other Towa-speakers at Jemez Pueblo.

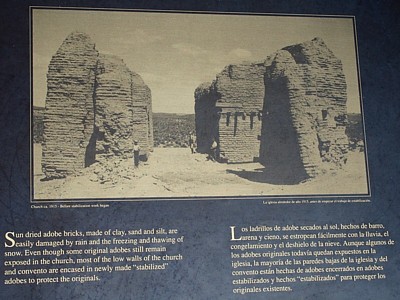

The clay, sand, and silt adobe bricks are susceptible to natural

forces. Considerable restoration encases most original colonial

walls. Even the restoration reveals different epoch of building and

variation in erosion. This early photograph illustrates the amount

of restoration/reconstruction.

The museum displays the long chronology of the Native Americans, and

the recent Contact era, using artifacts and interpetations.

Archaeologist Albert Vincent Kidder brought the fledgling science of

archaeology to Pecos in 1915. Kidder tested the theory of stratigraphy

on the Pecos trash middens. After 12 field seasons, he had established

a relative chronology for the American Southwest based on ceramic

variation, in styles, materials, and techniques. At the 1927 Pecos

conference, he and other scientists established the classification

sytem still in use today, from Basketmaker to Puebloan periods. The

Pecos Conference tradition continues annually.

Early historic Tewa bowl with cloud and lightning symbols.

Glaze II/III jar.

Glaze I red jar.

This bisque ware vessel from Pecos evidences trade/exchange with the

Rio Grande area.

![]()

![]()