|

Companion Articles:

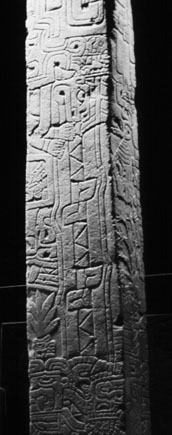

The Tello Obelisk, a Chavín

de Huantár Sculpture

©2000 by James Q. Jacobs

The

Tello Obelisk is a prismatic granite monolith from the archaeological

site of Chavín de Huantár in north-central Peru. The Obelisk

features one of the most complex stone carvings known in the Americas

for its time. Chavín is situated at 3,150 m in the upper Monsa

River drainage, between the Cordillera Blanca and the Cordillera Oriental,

two of the three ranges in the Central Andes. Chavín is located

on a pass to the Callejón de Huaylas, a high elevation valley between

the Cordillera Blanca and the Cordillera Negra, the western range. Radiocarbon

measurements indicate that construction of the initial phase of monumental

architecture at Chavín, a U-shaped platform mound known as the

Old Temple, began around 850 B.C. The U-shaped platform frames a 40 m

plaza with, centered on the axis of the monument, a 21 m in diameter sunken

circular court lined with cut stone blocks featuring low relief carvings.

The Tello Obelisk was probably set in the center of this Old Temple sunken

court. In this setting the surrounding lofty, snow-covered peaks of the

Andes are visible towering above the monument.

|

The correlation of the Tello Obelisk to the Old

Temple is supported by stylistic comparison with the Lanzón,

another important monolith at Chavín. The Lanzón remains

embedded within the Old Temple, securing its temporal placement.

The Lanzón and the Obelisk are unique exceptions to the three

groups of Old Temple sculpture at Chavín; ashlars carved

in flat relief, three-dimensional tenoned heads set into the exterior

stone walls of the platform mound, and mortars. The Obelisk was

discovered by Julio C. Tello during excavation of the site and thereafter

moved to Lima, Peru, where it is currently housed in the Museo Nacional

de Antropológia é Historía. The photographs

in this paper are from a transparency I took at the Museum in 1988.

|

The Obelisk, a slightly tapered quadrangular solid, is

2.52 m tall with about 0.32 m and 0.12 m wide sides. A notched upper section

narrows the upper one-eighth of the two wide faces to about 0.26 m. Excepting

the notch, the four sides are planar. The full girth at the base is near

1 m, and the form uniformly tapers to about 0.87 m in girth at the notch.

All four sides or faces are sculpted in bas-relief carvings from top to

bottom (Figure 3). The sculpture includes figures in relief with a background

plane and subtractive sculpting of the foreground plane. The carvings

are described in greater detail below.

The Tello Obelisk is a white granite sculpture. At Chavín

the nearest source of granite is located at 18 km distance from the ruins.

Granite, one of the most common of the igneous rocks, is an entirely crystalline,

unstratified, dense, and immensely hard, chisel-resisting stone. Granite

is composed of quartz, mica, hornblende and feldspar. Feldspar is the

most abundant mineral in granite. The higher the quartz content, the harder

the granite. Granite is one of the most durable of stones, and is highly

resistant to the destructive forces of the elements. Granite is therefore

not only quite difficult to carve but also can take a very high polish.

An advantage of granite is its beautiful and consistent color. The color

of granite depends on the feldspar it contains, as well as the quartz

and hornblendes. In my Kodachrome transparency the Tello Obelisk is a

light fulvous sienna in color (perhaps shifted towards yellow by the indoor

lighting).

During the Early Horizon (900 B.C to 200 B.C. in

the Rowe-Lanning chronology) the prehistoric cultures of Peru lacked metal

tools. If no appropriately shaped stone is found one must be quarried.

To quarry raw material, blocks of stone need to be split by wedging. First

a series of holes are drilled in a straight line at close intervals. Wedges

are then driven into the holes, applying equal pressure along the length

of the split. Wooden wedges can be soaked to split the stone, and this

is the probable method used in ancient Peru. Wedge holes have been found

in ancient Egyptian quarries. Quarrying is followed by moving, lifting

and transporting. Given the distance from the quarry to Chavín,

the mountainous terrain and the lack of draft animals or wheels, it is

likely that roughing out the shape of the stone preceded transport to

the site. After quarrying each step involves removing material from the

original mass, an entirely subtractive process.

Just as metal wedges are used today to quarry blocks,

so also are metal tools used to carve granite. Material available

for tools is an important factor in methods and process. In Neolithic

Peru the sculptures had to be carved with hard stones. Stone is

worked by a series of simple steps. The two basic categories of

stone sculpture tools are percussion and abrasion tools. Percussion

tools are either hammers and chisels in combination or axes. The

heaviest hammers used today, sledge hammers, weigh about 2 kilos.

Carving granite is typically accomplished using a chisel set perpendicular

to the surface. The harder the stone the more perpendicular to the

surface the chisel needs to be.

Abrasion tools work by rubbing away material. Abrasion

tools are used to cut, shape, smooth or polish. Polishing is accomplished

by fine abrasion and requires a considerable expenditure of time

and energy. The Chavín carvings have lustrous surfaces, evidencing

polishing with a series of abrasives. During abrasion the sculpture

is typically soaked with water and abrasive stones, such as silicon

carbide, are applied in descending degrees of grain and of hardness.

Very fine sand is used as an abrasive for the highest degree of

polish.

The properties of stone always have an influence

on the art. Granite sculptures rarely have undercuts because it

is a hard, brittle material, prone to breaking during percussion.

Once a piece breaks away from a sculpture it cannot be replaced.

The planar form of the Tello Obelisk is well suited to the material.

There are no truly sharp edges and all the lines, grooves, incisions

and corners are at least somewhat rounded. The relief difference

between the background plane and the face is shallow, perhaps 3

cm at most. The durability, internal consistency, strength and hardness

of the granite also makes possible the overall form, the narrow,

tall obelisk shape. |

View

Larger Image View

Larger Image

345 x 875 pixels

68 Kbytes.

|

Neither the material, the form, nor the technology have

attracted the attention of the many writers who have focused on the Tello

Obelisk to the same degree as the iconography. The fame of the Obelisk

is attributable to the iconographic richness of Chavín art, and

the obelisk is the most iconographically complex of the Chavín

objects. It is also arguably the most unique in iconographic content.

Chavín art is basically naturalistic, and the major subjects are

humans, avians, snakes, felines, other animals, plants and shells. Idealized

forms of these elements are covered with abundant smaller elements, often

as metaphorical substitution of body parts. A typical and well known example

is the substitution of snakes for hair on the Lanzón.

Another unique feature of the Tello Obelisk’s iconography

is the geographic scope of its elements. The Chavín civilization’s

interaction sphere included Peru’s three major ecological zones,

the desert coast, the highlands and the humid tropical forests. Chavín

is located at an important route from the Pacific Coast to the Amazon

Basin. Via the Santa and Monsa Valleys it is possible to cross the Andes

by crossing only one high pass. Chavín is located on this route

and the Obelisk’s iconography reflects the natural world in the tropical

lowlands, the coast and the highlands. Chavín’s unique interregional

synthesis is also reflected in the monumental architecture. The Old Temple

combined the U-shaped pyramid and the sunken circular court, diverse coastal

traditions, with stone masonry unique to the highlands. The antecedent

for relief carvings also has many coastal antecedents, in both stone and

plaster. Chavín’s iconography and architecture is seen as

an unprecedented unification of previously heterogeneous elements. This

is particularly the case with the Obelisk.

The Obelisk features, in two representations, a zoomorphic

figure dominated by cayman attributes. Caymans are found in the low tropical

forests. The carvings convey a single composition in several narrative

units. Lathrop referred to the figures as a primordial deity and the "overarching

cosmological symbol in the culture of Nuclear America." The cayman

is an important component in the "Tree of Life" figure in Middle

American iconography, where it is usually depicted in a descending, or

partition posture, as the base of the tree and with its tail replaced

by vegetation. Campana believes the Tello Obelisk narrates a cosmological

myth. Wheatley sees the Obelisk as a very complete and detailed model

of the cosmos. While the speculations about the meaning of the iconography

are intriguing, I think the meanings will always remain in the realm of

the unproven. Nonetheless, I find it significant that the symbolism evokes

meaning to those who view the iconography today.

These cosmogonic interpretations arise in part from the

diverse representations of life forms in the imagery, and in part from

ethnographic analogy and contemporary myths. The two great cayman representations

are nose upright and, in scale, are nearly the size of the Obelisk. A

harpy eagle rises above the snout of one of them, giving the impression

of a sky element at the top of the monolith. The water element is insinuated

by the cayman and also by Spondylus and Strombus shells,

elements from the Pacific Ocean. Cultivated plants of Amazon Basin origin

are associated with the heads, mouths and noses of faces with pronounced

canine teeth, possibly jaguar representations. The Obelisk features the

largest mouth emblem of all Chavín mouth depictions, and has 15

exaggerated large mouths among the 50 mouths featured. The many faces,

mouths, plants, animals, anthropomorphs, shells, snakes, and geometric

forms fill the space on the monolith and cover the body of the cayman.

Stone itself can impart meaning to an object. Granite,

as the hardest locally available stone, conveys a message of immutability.

It also points to the probable desire of the monuments creators to hewn

a long-lived object. The shape of the object, especially in relation to

possible function, may also impart some meaning. If the slender monolith

was used as a gnomon to tell diurnal and seasonal time the imagery may

be related to the seasonal renewal of life or have meaning within the

context of the passage of time. Within this context the very ancient life

form of the cayman, and the very recently evolved life forms of domesticated

plants combine to present a possible representation of the changes in

life in relation to time, a concept more in keeping with a "Tree

of Life" interpretation and an understanding of evolution and the

interrelationships of all life forms. The obelisk also has the form of

a sprouting plant shoot.

Meaning can also be sought in the object’s location.

The Tello Obelisk was, in all probability, located on the same, central

east-west axis as the Lanzón, the only other prismatic granite

sculpture at the site. This axis aligns facing sunrise (103 degrees east

of north), reinforcing the interpretation of the monolith serving as a

solar gnomon. Lathrop regards the Tello Obelisk’s location as a material

representation of an axis mundi, a placemark representing the center place.

The configuration at Chavín is reminiscent of the configuration

at Tiwanaku, where a millennium later it is repeated by the Ponce monolith

inside the Kalasasaya monument, and a tall, slender monolith in the sunken

court, in front of and centered on the Kalasasaya axis and aligned to

the Equinox sunrise. This correlation reinforces the possible relationship

to time.

The Tello Obelisk is an intriguing artwork worthy of close

study. While its interpretations may never be fully supported, it definitely

evidences the complexity of the iconography of its makers. The Obelisk

forces us to ponder the thoughts of its makers. The intense overlays and

metaphorical substitutions of so many diverse aspects of nature make us

question what its makers thought about the relationships of these life

forms. Perhaps in so doing the Tello Obelisk is carrying out the intended

function of its creators, to serve as an immutable testimonial about the

relationships they observed in the diverse environments of desert, mountain

and jungle, and to stimulate those who view the imagery to contemplate

life’s relationships. If so, this is a more impressive accomplishment,

by my thinking, than the laborious technological feat of its creation.

Bibliography:

Burger, Richard L., 1992. The Sacred Center of Chavín de Huantár,

in The Ancient Americans, Art from Sacred Landscapes, Edited

by Richard F. Townsend, The Art Institute of Chicago, Prestel Verlag,

Munich.

Burger, Richard L., 1992 Chavín and the Origins of Andean Civilization. Thames and Hudson, London.

Campana, Cristobal 1995 El Arte Chavín, Analisis Estructural

de Formas é Imagenes. Universidad Nacional Federico Villareal,

Lima.

Lanning, E. P. 1967. Perú before the Incas. Prentice-Hall,

Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Lathrop, Donald W. 1982 Complex Iconographic Features by Olmec and

Chavín and Some Speculations on their Possible Significance.

In Primer simposio de correlaciones antropológicas andino-mesoamerican. Edited

by Jorge Marcos and Presley Norton, pp. 301-327. Escuela Politécnica

del Litoral, Guayaquil.

Lathrop, Donald W. 1985. Jaws: the Control of Power in the Early

Nuclear American Ceremonial Center. In Early Ceremonial Architecture

in the Andes, Christopher B. Donnan, Editor, pp. 241-267, Dumbarton

Oaks, Washington, D. C.

Moseley, Michael E. 1992 The Incas and their Ancestors, The

Archaeology of Peru. Thames and Hudson, London.

Olsen Bruhns, Karen 1994 Ancient South America. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

Penny, Nicholas 1993 The Materials of Sculpture. Yale University

Press New Haven.

Rich, Jack C. 1947 The Materials and Methods of Sculpture. Oxford

University Press. New York.

Rockwell, Peter 1993 The Art of Stoneworking: a Reference Guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Rowe, J. H. 1962 Stages and periods in archaeological interpretation. Southwest Journal of Anthropology 18:(1), pp. 40-54.

Timberlake, Marie 1988 The Cayman in Chavín Art: A Re-evaluation. Thesis (M.A.), Arizona State University.

Wheatley, Paul 1971 The Pivot of the Four Quarters. Aldine

Publishing Company, Chicago.

|