Understanding Chavín and the

Origins of Andean Civilization

©2000 by James Q.

Jacobs

Chavín was once compared to the Olmecs and

depicted as the Mother Civilization of the Andes. The

term Chavín has been applied to a developmental

stage of Andean history, to an archaeological period, to

an art style and to a hypothetical empire.

Chavín has been interpreted as a culture, a

civilization and a religion.

The idea of a Chavín horizon was proposed by

Julio Tello. In the 1930s Tello claimed that

Chavín was Peru's oldest civilization. His

definition of a pan-regional Chavín culture

included attributes of ceramics, architecture and

sculpture. The incorporation of sites with some

Chavín characteristics eventually led to a

perceived culture spanning two millennia and reaching

from Ecuador to Argentina. Tello's criteria has

since been narrowed and recent research, especially

radiocarbon dating, has refined understandings of

Chavín and regional site relationships.

In the 1960s John Rowe's Andean chronology defined the

Early Horizon as the time beginning with the first

appearance of Chavín influence in Ica. This

arbitrary criteria requires a definition of

Chavín influence and a clear understanding of the

Chavín style horizon. The style can be

unevenly documented on the coast from Lambayeque to Ica,

and from Pacopampa to Ayacucho in the highlands.

Adhering to Rowe's definition presents some

problems. For one, new dates at Ica might change

the Andean chronology. And, as has been

subsequently determined, it also means that

Chavín influence precedes the first sculptures at

Chavín, the content of which defines the style,

and precedes Chavín itself.

There are several important areas to consider in

assessing the role of Chavín in the origins of

Andean civilization. Landscape context is an

important aspect of all cultural development

trajectories, and particularly so at

Chavín. In early Andean communities

dependence on more that one life zone promoted

interaction, exchange and interdependency, a pattern

first evidenced in the coastal valleys where the

exchange pattern involved the series of

elevation-stacked ecological zones beginning with

maritime resources and extending inland to agricultural

and pastoral habitats. An excellent example is

found in the Casma Valley , at Moxeke, 18 km from the ocean, where almost all animal protein was maritime.

Chavín civilization may be the best early

expression of a similar pattern on a larger ecological

scale, that of interaction between the three major

ecological zones, the coast, the highlands and the

tropical forests.

Chavín de Huantár, the archaeological

site, is uniquely situated in the region of the

Callejón de Huaylas, where there are only two

ranges in the Andes, rather than the usual three.

The glaciated Cordillera Blanca has, in a 180 km long

span, a few passes, all over 15,000 feet in

elevation. Chavín de Huantár, midway

between the coast and the jungle, is located on a route

accessing the very extensive Marañon

drainage. Almost all the large rivers of the

central Andes flow to the Amazon drainage. The

Callejón de Huaylas' Santa River drains to the

coast, transecting the Cordillera Negra. Via the

Santa Valley it is possible to cross the Andes by

crossing only one high pass.

Chronology is also significant in assessing

Chavín's presumed influence. Tello

considered Chavín to be older than the coastal

sites with Chavín style, and viewed the stylistic

evidence as indicating Chavín's expansion.

John Rowe's 1962 stylistic seriation of sculpture and of

Ica ceramics provided only a relative chronology for

Chavín. Peter Rowe's subsequent stylistic

assessment of chronological placement of coastal and

highland sites concluded that there was gradual

expansion of influence from Chavín.

In 1979 Burger clarified the ceramic sequence at the

Chavín site, naming three sequential phases based

on 11 stratigraphic excavations. Burger also

analyzed 20 carbon samples, half each from the monument

and the settlement areas. Radiocarbon measurements

established an absolute chronology for Chavín de

Huantár, spanning from 850 BC to 200 BC. By

500 BC Chavín de Huantár was a flourishing

center double in size from the time of first

construction 300 years earlier. Most of the

construction dates to 400-200 BC. Around 400 BC

the monument was remodeled and greatly expanded and the

settlement increased to over 40 ha and about 1.2 km in

length. Population may have reached 3000, making

Chavín one of the largest highland centers in the

Andes.

Radiocarbon dates from coastal sites with Chavín

style ceramics, sites that had been interpreted as

provinces of Chavín, were compared by

Burger. Three widely distributed major sites were

selected, Las Haldas, Caballo Muerto and Ancón

near Garagay. Monumental construction at Las

Haldas dates from 1190 BC to 900 BC. At Caballo

Muerto the constructions that resemble Chavín

also predate Chavín, ranging from 1730 BC to 850

BC. The presumed Chavín influenced ceramic

phases at Ancón dated from 1345 BC to 810 BC,

with a mean of 1074 BC. These coastal monumental

centers prospered between 1700 BC and 900 BC, while the

earliest constructions at Chavín dates to about

850 BC. The coastal sites are older than

Chavín. The architectural features and

iconographic style at Chavín de Huantár

actually developed elsewhere, and the direction of

influence is the reverse of what was first assumed.

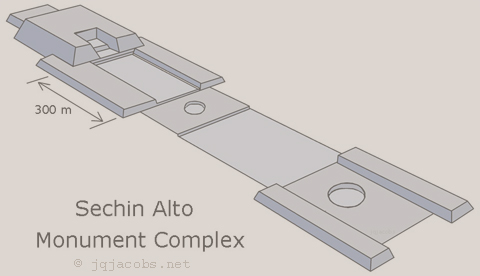

Relative comparison of site size can illustrate or

define possible relationships. The Chavín

monument is less than one-tenth the size of

Sechín Alto, in the Casma Valley. The

Casma has the largest and most elaborate Initial Period

constructions. The shortest route from

Chavín to the coast, across the Cordillera Negra,

descends into the Casma Valley. Sechín Alto

covered 300-400 hectares, and it is just one of several

monument precincts in the Casma drainage.

Sechín Alto is also one of the largest

architectural complexes in the world. The monument

complex alone extends nearly 2 km. The entire

community of Chavín would easily fit in

Sechín Alto's central plazas. Also in the

Casma Valley, Las Haldas covers about five times the

area of Chavín. At Moxeke the monument

complex alone extends over a kilometer in length, with

70 platform mounds flanking the sides of the central

plaza. Other coastal monument complexes also

greatly exceed Chavín in size. Of course,

Chavín features unprecedented architecture due to

its remarkable engineering, quality masonry and very

fine sculptural stone art, in contrast to mostly earthen

and adobe plaster over stone monuments on the

coast. This may be a response to the local climate

more so than an indicator of relative importance.

Socio-political organization changes dramatically

during the Early Horizon. One expression of the

preceding Initial Period social pattern is found in the

monumental architecture. Distinct style areas of

monumental architecture are seen, with the central,

north-central and the north Peruvian coast having

distinct monument styles. Each of these zones were

represented by a major site in Burger's radiocarbon

comparisons. Early regional political

relationships may be evidenced by these style zones and

by concentrations of or by extremely large inland mounds

in the Moche, Casma and Chillón-Rimac

Valleys. Sechín Alto evidences over a

millennium of construction.

There is little evidence of economic or social

stratification during the early Initial Period in the

Casma Valley. Evidence of some stratification is

seen by the late Initial Period, with a difference in

two groups of dwellings. Dwellings attached to the

monument precinct were of more substantial

construction. New social classes may have emerged

by the end of the Initial Period, coincident with the

end of massive public architecture projects. The first

settlements to evidence social differentiation are the

Preceramic sites of Rio Seco, El Aspero and Bandurria,

communities of up to 3,000 population, a size comparable

to the maximum at Chavín.

Stratification is evidenced at Chavín in the

settlement pattern. Rich burial accompaniments in

northern highland areas during Chavín's last

phase evidences status differences, reinforcing the

status interpretation of the settlement differences at

Chavín. Craft specialization also appears

in households. The first evidence of urbanism and

these social changes date to the last phase at

Chavín only. Burger calls the site

proto-urban at this time.

Trade is an important factor in the development of

Andean civilization. Interregional trade rose

sharply during the Early Horizon. Chavín's

interaction sphere, as a supra-political entity, is

characterized by a new scale of interaction and exchange

of goods and ideas. Exchange items included

pottery, shell, stone resources, wool, textiles, metals,

and dried fish. The more unified iconography may

be related to this social change.

Chavín's location allowed flow of and/or control

of trade between major environmental zones. Long

distance trade fueled Chavín's success and

growth. Trade was dependent on llama

conveyance. Domesticated llamas first appear with

frequency at multiple sites outside their natural range

during the Early Horizon.

By 400 BC sophisticated economic systems involving

distant trading had been established and roads were

developed. The several regional spheres of

interaction during the Initial Period became a single

economic interaction sphere spanning nearly 1000 km,

from Pacopampa to Pata de Huamanga, and including

coastal, highland and the eastern Andean slopes.

Studies sourcing obsidian evidence a sharp increase in

long-distance trade. Obsidian from the Quispisisa

source, 450 km south of Chavín, reached the

northernmost extent of the Early Horizon exchange

network. Of the three phases at Chavín, the

final Janabarriu phase reflects the most extensive

communication networks, when obsidian use at

Chavín increased 500 fold. Products from

Ecuador and Chilé found their way into the

exchange network. At the same time the pattern of

interaction is uneven, indicating local determinism.

Technological innovations appear suddenly and diffuse

over a wide area during the Early Horizon. In

textiles, use of camelid hair in cotton textiles, dying

camelid hair, textile painting, resist painting,

discontinuous warps, warp wrapping, and the heddle loom

transformed the Andean textile tradition. In gold

metallurgy three dimensional forms, soldering, sweating,

welding and silver-gold alloys appear. Wide

distributions accompanied these technological

advances.

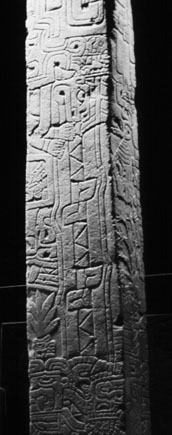

Chavín's elaborate iconography is

found on hammered gold and textiles as well as on

ceramics, stone sculpture and clay friezes.

Chavín iconography represents an unprecedented

unification of previously heterogeneous groups, yet

without total cultural homogenization. A wide

range of groups in the mid-Early Horizon modified

traditional ceramic styles, yet the pottery continues to

display regional style variations. In contrast,

textiles of the Chavín horizon do not display

regional distinctions in technology or style, and are

therefore an excellent horizon marker in areas of good

preservation.

The Early Horizon panregional ideological codification

reflects a shared ideology and a far wider group

identity than during the Initial Period.

Chavín de Huantár's iconography reflects

an ideological system incorporating material from the

tropical lowlands, the coast and the highlands.

Nonetheless, the hypothesis emerged that Chavín's

stylistic homogeneity, over a wider area than all

previous cultural styles, resulted from a single point,

rapid dispersal of the style. There was a

long-standing consensus among anthropologists and

archaeologists that Chavín style expresses a

religious ideology and represents a religious

diffusion. Rafael Larco viewed Chavín as a

pilgrimage center erected by members of a feline

cult. Rebecca Carrión called the

Chavín empire a religion that spread a

homogeneous art style. Gordon Willey interpreted

the diffusion as a peaceful spread of religious

concepts. The basis of these assumptions, rapid

dispersal from a single source, has been undermined, yet

the consensus interpreting Chavín iconography as

religious remains.

The

design features of the Chavín monumental

architecture have their origins in coastal sites.

Chavín's building style is unique and

synthesized. Chavín's Old Temple, the

initial monument, combined the architecture of the

central coast U-shaped pyramids and the north-central

coast sunken circular court, a synthesis that was seen

earlier at Sechín Alto. Some of the iconography

at Chavín is found in the clay friezes on the

earlier coastal monuments. The antecedent for low

relief stone carvings decorating the monument exterior

dates to 1200 BC at Cerro Sechín in the Casma

Valley. After 500 BC decorated cylindrical

columns, an architectural element from the northern

highlands, were added.

What was the function of Chavín? Hundreds

of decorated ceramic vessels for eating and drinking

evidence group feasting. The pottery includes

items created hundreds of kilometers from the site,

indicating possible usage by distant communities.

Coastal mussels and fish were found with the pottery,

further evidencing distant contacts. Chavín

art is basically naturalistic, lacking in political

content and devoid of historic personages or

scenes. While the consensus is for a religious

function, Karen Olsen Bruhns writes that "There is

little direct evidence concerning Chavín

religious beliefs or practices..." There is also

little direct evidence of political function.

It seems that the preeminence of Chavín de

Huantár continues to be exaggerated due to,

first, the early misidentification of Initial Period

iconographies as Chavín, second, the need to use

stone in the highlands resulting in differential

preservation, third, the sequence in the discovery and

investigations, fourth, changes in available methods,

particularly radiocarbon dating, and fifth, the

presumption of a Chavín religion.

Interaction and exchange seem adequate explanations for

the developments at Chavín in such an

economically significant location. The significant

increases in trade parallels the chronology at

Chavín, therefore I see exchange during the Early

Horizon as a very plausible explanation for the

diffusion of a universalist iconography and art style.

During the third century BC a disintegration of the

Chavín interaction sphere is evidenced by halting

of construction, replacement of Chavín style

ceramics by local styles, widespread construction of

hilltop fortresses in the highlands and coastal valleys,

a decline in interregional trade and intensified

socioeconomic stratification. Two centuries

after Chavín's fluorescence the hypothetical

civilization waned. |