Part Two -- JUAN OLD CHEVY AND JACKASSES TO THE ANGELS

or

ANAHUAC AL DEDO

Mexico. Jan. 3. Ciudad Juarez. Enjoying lunch at Cafeteria Vyc,

across from the Futurama Shopping Mall. Wow, it feels great to be in

Mexico. What a contrast! My only hitch so far was in the back of an

ice delivery truck. We crossed streets named for Central and South American

nations. I didn't notice Perú. We avoided the fast thoroughfares by

weaving through back streets and even detoured around an overpass because

their old Chevy has only one remaining gear. From atop the truck I enjoyed

an unobstructed 360 degree view of deteriorating adobe housing, the

bull fight stadium, the Ford dealer and an overflowing garbage truck,

all slowly. At the several ice delivery stops the crew bought cold beers.

I declined descending to partake of beer and mota.

Mmmm. Great enchiladas. In all the USA there are no Mexican restaurants

with decor like this, consisting entirely of one Emiliano Zapata picture.

Ranchera music fills the small room. Due to low grade diesel fuel and

no pollution controls thick black exhaust and loud mufflers await on

Avenida Tecnológica.

Jan. 4. 10:28 a.m. Saucillo, Estado de Chihuahua. In a coffee

shop. Yesterday José, my 375 km. Juarez-Chihuahua ride, gave

me his Mexico City address and invited me to stop and stay whenever

I might pass through. He also gave me a 1907 penny as a friendship token.

I gave him a little soapstone pebble which I found near an 11,000 year

old human occupation site in California. Because he smoked cigarettes

I got a headache.

The first truck I thumbed thereafter crossed most of Chihuahua City.

While walking to the edge of town people sought to converse and twice

people in cars stopped to ask where I'm going. The evening street was

filled with people. The atmosphere was warm and friendly. The first

motel offered rooms costing $4.50 U.S. "I'll take it."

During this morning's ride, from Chihuahua to Saucillo with two irrigation

project engineers, we stopped at one's home for a great breakfast. Such

openness and hospitality is a pleasant surprise, even on this, my tenth

Latin America trip. I'm enjoying the language change. My Spanish is

rough after a two year abstinence. An occasional English word escapes

me in mid-sentence and I have vocabulary hesitancy. Hitchhiking provides

ample practice.

It's another beautiful, sunny day, as has been each one since the Colorado

Plateau. This morning it was chilly before sunrise. One negative, especially

disadvantageous to the hitchhiker, is the thick black diesel exhaust

typical south of the border. I'm extending my breath holding skill.

One must pay close attention and take a deep breath just before a foul

diesel passes. It's necessity, not sport, when left standing in a toxic

cloud.

11:28. Ojinaga Junction. The sun is bright. It seems like summer.

On the slaughter house wall is written: "We buy horses and burros."

The smell is unique. I arrived here after two rides, one with seven

hitchhiking children on a layer of alfalfa bales in a compact pickup

weaving at slow overloaded pace and the other also in the back of a

small pickup, but with a bible-toting preacher-hitchhiker.

Many people, with incredible courtesy, are hand signaling their reasons

for not stopping. All fingers together pointing up means too full. Pointing

sideways means going to turn off. Pointing down means staying here.

Pointing down while making a circular motion means just driving around.

Many passing vehicles are very full. One time years ago in Southern

Mexico someone stopped and apologized for having too full a vehicle,

only to then fit me in anyway. How many people fit in a Mexican car?

Always one more! How many in a bus? No one is certain yet!

12:39. Still waiting for a nice person with a vehicle, no matter

how full. There seems no shortage of nice people. Oscar Robinson, a

local man, stopped to chat and asked if I needed anything, "Food, drink,

money?" He gave me his address and said to stop if ever I need anything,

anything at all. We spoke of his trips to New Mexico where he worked

while an illegal alien.

Two young girls who live in the nearest house brought a delicious tangerine

from their aunt's tree, saying, "If we can offer you anything, we live

right here."

2:16. Ciudad Jimenez. In a restaurant surrounded by curious

people and just off a ride in a cargo truck. The moment I boarded I

was offered a bean and beef burrito and a share of a soda, half the

driver's lunch. What courtesy!

6:28. The Durango junction. After lunch I didn't bother to throw

the thumb at one of the first vehicles to pass, a very slow, old diesel.

The driver hand signaled, "What you doing?"

I signaled, "I'm hitchhiking."

He stopped. His name is Nacho. Writing in large red letters on the

wall of a building we passed said "Reagan" and "Gringos" out of Central

America.

8:36. Torreón. Finding a ham and avocado sandwich with a soda

for only 45¢ was a pleasant surprise. I'm still adjusting to the

big differences in currency and values. Presently I'm in Room 50 of

the Hotel Hidalgo, for which I paid 2 dollars and received the price

of dinner in change. A cockroach is exploring the floor so you know

what squalid quarters I'm exploring. The streets in Torreón tonight

are a multitude of humans and diesel engines in a sea of toxic exhaust.

Deep in the hotel it's respiratable and quiet except the conversation

of laborers stoking the hot water boiler with cordwood.

Jan. 5. 9:21 a.m. I awakened early to painful intestinal contractions

and awakened again and again for the same reason. I got up, had a bout

of diarrhea and the cramps have stopped. It feels like a thorough purge

only.

2:30. Having lunch somewhere north of Fresnillo. My first ride

down the Pan-American this morning was a four wheel cart drawn by a

pair of jackasses. I couldn't resist requesting a ride of the two Native

drivers. We spoke of weather and crops during the 4 kilometer ride to

their small village, Los Angeles. I told them I was born far to the

north, so far that the season is too short to grow corn for mature seed.

The driver disbelievingly asked what the people ate. I replied that

instead of tortillas they eat potatoes.

"Do they eat with spoons?" he asked. I explained that forks are preferred

and that my people don't know how to eat with tortillas instead of silverware.

They were amazed. True natives indeed.

The next ride, a slow diesel truck, had a gas mask on the dash. I wonder

if my gastrointestinal cramps were caused by a high dose of diesel fumes.

Riding in a slow diesel is preferable to riding behind them.

The North American desert is vast. Since Utah all has been desert.

Today's surroundings have marginal dry land farming interspersed with

the cactus and greasewood.

When I approached this restaurant a group of children encircled me

asking for dollars. They are busy devouring leftovers and emptying sodas

at two just vacated tables. A car is arriving and they are now rushing

outside, hoping to scam a few coins for window shining.

6:57. Hotel Condensa, Zacatecas. I'm splurging for comfort and

a private bathroom with shower; this room costs an expensive $6.40.

I'm tired of the truck noise and exhaust and a bit ill still with an

occasional cramp. Today, for the first time, I miss my kitchen and refrigerator,

tofu and mushrooms, yogurt and granola. My mood reached a low point

and then I caught today's last ride, a reinvigorating encounter with

a Maya Indian from Yucatan who gave a lengthy discourse on the perils

of the people leaving the land and becoming materialistic. While walking

into town I passed a park with greenery and blossoms, thereupon realizing

that today I crossed the tropic line. A joyous mood has been somewhat

restored.

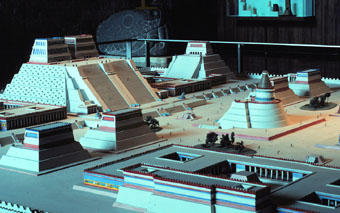

Jan. 7. 9:13 a.m. San Juan de Teotihuacan. To enter the Teotihuacan

Valley and witness the awesome proportions of the pyramids, immense

geometric ruins rising like mountains from the valley floor, is truly

an impressive experience to even the return visitor. Such extraordinary

products of human hand and mind inspire awe and wonder and many a question.

Teotihuacan was once one of the largest cities in the world and the

largest and most influential of all early North American cities. It

was the principal center for a large area of Central Mexico beginning

over 2,000 years ago and until its abandonment around A.D. 700. The

12 square mile urban center of 100,000 plus people was built on a planned

grid system, considered unprecedented in America. The principal axis,

oriented 15 degrees 28 minutes to the east of true north, is four miles

long and bisected by a perpendicular avenue of the same length. The

city's surveyors achieved a near perfect right angle. I've studied the

fresco painted masonry walls and walked the ancient concrete floors

of this city before, yet I look forward to further exploration.

Yesterday I traversed the states of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Queretaro,

and Hidalgo. This morning two fast rides brought me to this village

a few kilometers from the pyramids. Between rides I was deposited within

the smog zone at a freeway junction and toll gate near metropolitan

Mexico City. I had to jump out of a ride amidst rows of stopping and

starting diesels. The scene defies description. Imagine the darkest

exhaust ever witnessed, perhaps from an earthmover, except issuing from

below, behind, or beside each bus. Add a large cloud billowing with

each start and gearshift. Then all that's left to envision is the toll

house and three stop and go traffic lanes in each direction filled with

crammed full bus loads of morning commuters. So there I was, holding

my breath and making my way to the edge of that lethal scene. I could

barely see the surroundings. A prompt ride sped me out of the dense,

noxious cloud. Cresting the hill where the pyramid-graced Teotihuacan

Valley view is attained was compensation enough, believe it or not.

12:00. Cerro de las Maravillas. On a ridge top rock outcropping

hunting petroglyphs. I'm seated beside a hearth and an offering of four

cobs of purple corn. The Pyramid of the Sun is plainly visible 5 miles

to the east, though its immensity suggests a lesser distance. The other

monumental pyramid, the Pyramid of the Moon, is hidden by an intervening

ridge.

The so-called Astronomer's Chair, a petroglyphed boulder, is located

at the low end of this outcropping. One of a network of rock engravings

around the valley postulated to have astronomical significance, it is

perhaps the most distinctive of them. Faces outnumber the snake image.

Holes were drilled in the rock, perhaps for shadow sticks. The most

conspicuous image, more sculpted than incised, is a common figure in

Teotihuacan art, the goggle-eyed and fanged face of Tlaloc, the so-called

god of rain. Is the valley's network of petroglyphs millennia older than

the pyramids? Quite possibly yes.

1:18. Teotihuacan Archaeologic Zone. Restaurante Los Pyramides,

the Museum Building. It's such a hot afternoon that I've opted for a

cold, fresh pineapple juice before studying the museum. Beyond the windows

many pyramids fill the view.

While walking back from the astronomer's chair I encountered a man,

we made eye contact and he hand signaled, What?

"Que Maravillas hay por aqui." (What wonders there are here.)

"Si, hay no," (Yes there are, aren't there,) he said as he made large

circles around his eyes with his fingers, in imitation of the Cerro

de las Maravillas goggle-eyed Tlaloc I presumed.

I placed my fingers on my chin. He smiled and said, "Y ahora, a donde?"

(And now, where to?)

"A subirlo." (To climb it.)

5:11. Pyramid of the Sun, facing the sun and Cerro de las Maravillas.

From this perspective the equinox sun sets over the astronomer's chair.

This over 40 million cubic feet adobe brick pyramid rises 230 feet from

a base 738 feet per side, more or less. I walked up non-stop while counting

the steps, resulting in a tally of 243. The wind feels great. The weather

is different on the summit.

Atop the pyramid is a great place to meet comic souvenir peddlers and

other interesting people. I became involved in conversation with a group

of young Mexicans discussing the mathematical symbols and astronomic

data engraved on the immense Tenochtitlan calendar stone. Several of

us each had book excerpts on this same subject which we shared. As I

concluded translating an article from English a woman behind me asked,

"What do you know about Teotihuacan?" I had chosen this vantage to study

some Teotihuacan articles

which I briefly lent her. Conversation followed regarding scientific

aspects of pre-Columbian civilization, especially the astronomic tables

deciphered in the few surviving Mayan screenfold books. She and her

two fellow South American companions, all Boston educated, are doing

preliminary fieldwork for a film about what was lost and destroyed by

the conquest of America.

I count fifty pyramids scattered below. How many more are overgrown

or destroyed? To the north the 490 foot wide Pyramid of the Moon rises

138 feet. Teotihuacan's principal avenue, the Avenue of the Dead, begins

at the Pyramid of the Moon, crosses the foreground and extends to two

miles just past the museum and then beyond. Visiting Teotihuacan means

long walks and high climbs, yet there is no evading the persistent vendors

and their purportedly ancient wares.

7:34. San Juan de Teotihuacan. I've taken a room at the only

hotel. The restaurants are many and after a cursory inspection tour

I selected the "Zully." I like the red and white carnations with green

table cloths, los colores nacionales. The cassette player is blasting

"Hay tanto amor." This is truly Mexican. The first course, consume de

pollo (chicken soup,) just arrived in colorful floral china.

Just before the ruins closed I was photographing fresco murals below

the Palace of the Quetzal-Butterfly. Upon concluding a close up of the

"Eagles," I walked back to the "Jaguars" where sat the guard's wife

studying illustrations of the solar system. The guard, his wife and

I conversed and again I shared my Teotihuacan information. Their interest

in Teotihuacan archaeoastronomy was keen.

The tacos and the Spanish rice are great. The waitress and waiter arrived

together and as one held the tray the other served the courses. Only

the floral plate under the rice pudding bowl is mismatched. The chili

verde sauce is flavorful but hot. The pickled peppers are definitely

HOT! Great apricot juice and bread, but the peppers are still HOT. WOW.

"Would you like the mineral water with or without ice, Sir?"

I gave the beggar who came to the table a French roll slice. He was

86'ed. Not taking any chances, he quickly stuffed the whole bread slice

in his mouth. The stereo is blasting, "Anoche no pude llegar a ti."

On a shelf on one wall there are carnations, a burning candle and a

Blessed Virgin Mary picture. The topless lady calendar and stereo are

on another wall. "No dejame por otra cosa." Dinner, apricot juice and

mineral water: $1.42. The beggar awaits outside due to my hand signals.

8:39. At the panaderia, the bread store, I bought the man four

French rolls for a dime. What a smile that produced. He made strange

sounds but didn't speak. I'm sitting near the zocalo in the middle of

the central plaza after hunting postcards. The surrounding 100 or so

promenading and socializing people sound delightful.

The moribund municipal clock reads 5 to 12. This morning I stopped

in the municipal building to ask directions to Cerro de las Maravillas.

A group of village officials had not heard such a place name. Unable

to assist, one cautioned against going out into the countryside "amidst

the Indians." Another warned that because Indians cut weeds and clean

the fields they have machetes. Once in the countryside at what seemed

like the correct side road I asked an Indian driving a new pickup. He

told me exactly where to find the petroglyphs.

Jan. 8. 9:20 a.m. In a bus en route to Mexico City. I will spend

the day in the Museum of Anthropology, now minus 140+ pieces. On Christmas

Eve that greatest treasure house of American heritage was robbed of

more than 140 pieces of the most spectacular and beautiful prehistoric

art of the world. It seems an impossible tragedy yet it really happened.

Are the gold artworks now melted? Have the jades been recut beyond recognition?

In America this Navidad was not feliz. Will this crime be solved?

We are driving through thick exhaust smoke, protected inside the bus.

There are times and places where hitchhiking seems stupid. Mexico City

tops the list. Visibility is one half kilometer as we enter the suburbs,

or "barrios." I wonder about the life expectancy of street vendors and

traffic police.

Mexico City has changed through many centuries. Bernal Diaz del Castillo,

one of the conquerors of Indian Mexico, described arriving in Tenochtitlan

(Mexico City,) the greatest city in Anahuac (the One World,) on Nov.

8, 1519 as follows:

""...we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and the

other great towns on dry land and that straight and level causeway

going towards Mexico, we were amazed and said that it was like the

enchantments they tell of in the legend of Amadis, on account of the

great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all

built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the

things that we saw were not a dream .... I do not know how to describe

it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before,

not even dreamed about."

Bernal's statement is appreciable while visiting the museum.

11:06. Museo Nacíonal de Antropología. For $.0024

I rode the crowded subway across this vast metropolis and arrived at

10:20. Due to the Christmas Eve robbery several museum sections remain

closed and the museum will not allow photography until further notice.

My purpose includes photography so I've decided to stop again on the

return journey. Today I shall instead visit the nearby Chalpultepec

Palace to view colonial art, First a walk around the impossible to steal

200 ton stone sculpture of Tlaloc, a monolith of Teotihuacan vintage

decorating the front garden.

11:48. "Viva la America! Muera el mal Gobierno!" -- "Long live

America! Death to bad Government!" The famous Cry of Dolores, Padre

Miguel Hidalgo y Costillo, Sept. 16, 1810.

Chapultepec Palace is closed. Are they working on the security system?

Happy not to have wasted the long climb up Grasshopper Hill I entered

this adjacent museum, a National History Museum gallery about the Mexican

revolutions, beginning with Father Hidalgo's cry. Hidalgo was named

the first Captain General of the American Nation. On Oct. 19, 1810 he

decreed, "Siendo contra los clamores de la naturaleza el vender a los

hombres. Queda abolidas las leyes de la esclavitud." My translation:

"It is contrary to nature to sell men. The laws of slavery are abolished."

Hidalgo also decreed the abolition of tributes and large estates and

ordered the lands returned to the native communities. He was shot by

the authorities by firing squad in Chihuahua on July 30, 1811. The citation

against Hidalgo reveals much of history. It begins: "We, the Apostolic

Inquisitors against Heresy, Depravity, and Apostasy, in the City of

Mexico, states and Provinces of this New Spain, Guatemala, Nicaragua,

The Philippine Islands, their Districts and jurisdictions by Authority

Apostolic, Royal and Ordinary, Etc..."

Another priest, Father José María Morelos, replaced Hidalgo

and a constitutional decree for the Liberty of Mexican America was signed

on Oct. 22, 1814. Morelos was captured and imprisoned. On Dec. 22, 1815

he was shot. In April of 1817 Francisco Javier Mina arrived from Spain

where he had fought against King Fernando VII. His brilliant leadership

was short-lived as was he. On Nov. 11, 1817 he was executed, shot in

the back by firing squad.

The 1820 "Plan de Iquala," the plan of the three guarantees, proclaimed

the independence of Mexico. The three guarantees were: 1) Union of all

its inhabitants, 2) As the only religion the Catholic Church, 3) The

Imperial Crown would go to King Fernando VII of Spain or a member of

his dynasty. On July 21, 1822 Iturbide was crowned Emperor Augustín

I in the Mexican Cathedral. Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana proclaimed a

republic. Troops sent to battle Santa Ana by King Augustín joined the

rebel forces. Eventually the newly crowned Emperor was captured. Two

days before the second anniversary of his coronation Augustín I was

shot. The Federal Constitution of the United States of Mexico was approved

by a Constitutional Congress on Oct. 4, 1824.

My intent today was to study prehistory, not bloody modern history,

but this museum is educational indeed. There is more, I know, because

they have yet to mention Pancho Villa. Onward through time in this structure

means slowly winding downhill in a multi-storied circle, a "caracol,"

Spanish for snail. Uphill would be more appropriate.

"Any people anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the

right to rise up, and shake off the existing government, and form

a new one that suits them better. This is a most valuable--a most

sacred right--a right, which we hope and believe, is to liberate the

world,"

Abraham Lincoln, speech in the U.S. House of Representatives, subject:

The War on Mexico. Delivered January 12, 1848.

At about the time of that statement this very hilltop was under siege

by United States troops. The Palace defenders including military cadets

numbered a mere 800. President Polk defended his ordering the Mexican

invasion, but Lincoln had this to say about what provoked the hostility,

"The marching of an army into the midst of a peaceful Mexican settlement,

frightening the inhabitants away, leaving their growing crops and

their property to destruction, to you may appear a perfectly amiable,

peaceful, unprovoking procedure; but it does not appear so to us.

So to call such an act, to us appears no other than a naked, impudent

absurdity...the war was unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced

by the President."

A. Lincoln, July 27, 1848.

"...refusing to accept a cessation of territory, would be to abandon

all our just demands, and to wage the war, bearing all the expense,

without a purpose or definite object."

President Polk.

On Feb. 2, 1848, the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty was signed. Mexico conceded

Texas, California, and the Territory of New Mexico for 15 million pesos.

Today that many pesos will buy $35,714.28 U.S.-- one cheap tract home.

An 1853 revolution that ousted Santa Ana was overthrown by Benito Juarez,

beginning an era of reforms which included; 1) Nationalization of church

property, 2) Civil Marriage, 3) Secular cemeteries, 4) Religious freedom,

and 5) Civil registry. The War of the Reforms victory, on Dec. 22, 1860,

was also the 45th anniversary of Father Morelos' execution, about 50

years after Father Hidalgo's cry.

In 1862, France, England and Spain joined forces and invaded Mexico.

The first defeat suffered by the French on any front in 30 years on

May 5, 1862, the now infamous Cinco de Mayo, caused Napoleon III to

quintuple his forces in Mexico. The victorious French organized a monarchy

and Maximilian I was crowned. Article I, Title 1 of the Imperial Decree

states: "The form of government proclaimed for the nation and accepted

by the Emperor is a moderate monarchy, hereditary, with a Catholic prince."

Benito Juarez again led the revolutionary forces until victory in 1867.

Miramon and Mejía, Maximillian's general, and Maximillian were sentenced

to death by firing squad. On the morning of June 19 Maximillian asked

that his face not be damaged, with his hands he separated his beard,

opened his coat, pointed to his heart and said, "Here." Mejía, who had

bribed the firing squad with an ounce of gold, said nothing when he

saw the guns point at him also. So ended the short French era. Juarez,

a Native Zapotec Indian and Mexico's only modern Indian president, reentered

Mexico City in triumph.

Constitutional reforms and election fraud ruled Mexico until 1910.

It was an era of land being taken from the people, in some instances

displacing entire linguistic groups. By 1910 65 percent of the useful

land in Mexico was owned by 840 individuals, some with holdings exceeding

750,000 acres. Violent repression of agricultural strikes occurred in

1906 and 1907. The popular opponent candidate in the 1910 election,

Francisco Madero, was jailed in San Juan de Potosí before the elections.

Rebellion began when the fraudulent election returns reinstated Dictator

Porfirico Diaz. Prison escapee Madero and others formulated the Plan

of San Luis which called the nation to arms. After victory in 1911 Madero

was elected.

If this history isn't confusing enough, someone stole the next plaque.

Here's Pancho Villa at last. He helped overthrow Diaz. By Nov. 1911

the Plan de Ayala declared war on the Madero government because lands

had not been returned to the people. Emiliano Zapata led this agrarian

revolution. In early 1913 yet another group began warring against the

Madero government, the Porfiristas, cronies of dictator Diaz. They won,

Madero and V.P. Pino Suarez resigned and were shot. In this manner Victoriano

Huerta became dictator. On March 26, 1913, the Plan de Guadelupe declared

a revolution against Huerta. Revolutionary forces advanced towards Mexico

City on the railroad system from three directions. On June 23, 1914,

Pancho Villa won the Battle of Zacatecas. Huerta resigned when Obregón

captured Guadalajara. Pancho Villa's army of miners, cowboys, ranchers

and campesinos represented the most important element in the victory.

After an attempt to form a permanent government, war broke out between

the victors. The Pancho Villa-Emiliano Zapata faction lost. Venustiano

Carranza formed the government and decreed the Agrarian Reform Law nullifying

all land changes after Dec. 1, 1876. On the 5th of February, 1917, the

present Mexican Constitution was ratified, 106 years after Hidalgo's

cry.

2:42. The display ends in a tall circular tower containing the

Constitution, open to the page declaring the eight-hour work day. The

remainder of the museum, named 'The Struggle of the Mexican People for

their Liberty,' winds twice around the tower. Little did I realize what

a long gallery I had entered. The subject is overwhelming. At the exit

engraved in stone is written:

"Among nations as among men, respect of the rights of others is peace,"

Benito Juarez, 1862.

"I want to die a slave to principles, not to men,"

Emiliano Zapata, 1913.

We leave the museum, but not history, for history continues with our

lives.

Jan. 9. 10:27 a.m. The Tepexpan Prehistoric Museum, the site

where in 1947 geologist Helmut de Terra discovered the remains of a

human skeleton while digging for mammoth skeletons. Found face down

in the over 9,000 year old sediment of the Beccera Formation, the so-called

Tepexpan man was then the oldest human remains known in America. The

actual remains are exhibited in the Nacional Museum of Anthropology.

Helmut de Terra concluded the skeleton was of a male 55 to 65, of sturdy

build, about 5' 9" tall and needing dental care. Later studies concluded

that Tepexpan woman was under 30, 5' 3" tall and needing dental care.

A romantic account assumes that a mammoth stomped Tepexpan man into

the mud during a hunt.

Skeletons of mammoths, an extinct elephant much larger than the surviving

species, have been found in this area. Several scientifically excavated

skeletons were intermixed with spear points and butchering tools. Some

bones were found to have tool marks caused by slaughtering. In some

cases bone location indicated obvious dismemberment. It is known that

the humans who occupied the Valley of Mexico over 20,000 years ago butchered

mammoths nearly 10,000 years ago.

Hundreds of school children are flowing through the museum. The background

sound is a constant cacophony of little Spanish voices. On the wall

hangs a photo of the Tequixquiac bone, the sacrum on an extinct American

camel species carved to represent a dog's head. Found 39 feet below

ground, the sculpted bone is considered one of the oldest known artistic

efforts.

9:51 p.m. Jalapa, Vera Cruz. Cafe La Parroquía after seven rides

and ten hours on the road. I've eaten here before and been made to feel

at home this evening. On entering a waiter recognized me and extended

a warm welcome. Today's route featured viewing Mexico's two highest

peaks, 17,888 ft. Mt. Popocatepetl and 18,701 ft. Mt. Citlaltepetl,

both beautiful snowcapped volcanoes. It's cloudy and drizzling on this,

the Gulf Coast slope of the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains. Beginning

at the pass, from nightfall onward, the route was very foggy. An accident

involving a vehicle a few cars ahead of my ride stopped all traffic

for an hour. The driver of a small truck died. An 18 wheeler with a

flatbed missed a turn and crossed the oncoming lane. The small truck

crashed beneath the trailer. The victim was a young doctor.

Daily we accept risks in life, be that driving on a foggy highway or

mammoth hunting. My last driver was returning home after a month directing

earthquake relief efforts in Mexico City. Some of life's risks are not

of our own taking. Hitchhiking entails a few extra risks, like bad drivers,

bad vehicles, and riding in the back of fast flying vehicles, not to

mention the unknowns. In a sense one is placing one's life in the hands

of strangers. It's exciting. Today I spared a driver an accident by

shouting a warning. He quickly swerved and avoided a sideswipe.

Jan. 10. 2:36 p.m. The National Biotic Resource Research Institute.

I reviewed the Mycology Library's ethnomycological section. A wealth

of information is being copied for me at half the best USA price. I

enjoyed having lunch with mycologist and friend, Dr. Gastón Guzman,

who organized the valuable ethnomycology section. It's great to see

friends and find an excellent library in the same place.

We drank coffee and I must warn that a small cup of local brew is potent.

This is one of the best coffee regions in Mexico, if not on the planet.

Coffee is an important local crop. Dr. Guzman and the researchers at

this Institute have developed a methodology for producing the delectable,

edible oyster mushroom on coffee bean husk substrate. Until now this

husk was a waste product, a disposal problem and an environmental contaminant.

Daniel Martinez gave me a tour of the Institute's mushroom growing pilot

project. The researchers additionally found that the mushroom growing

process rendered the abundant and otherwise inedible coffee waste suitable

for use as livestock feed. Already one farm has started production in

nearby Coatepec. New projects have begun to experiment with maguey and

nopal waste products.

Jan. 11. 8:12 p.m. Valle Nacional village, Oaxaca state. Journeying

today involved six rides on five highways to arrive in 8 hours. In 4,680

f.a.s.l. Jalapa it was raining so I chose the road to the coast, descending

into drier lands through the papaya zone and past cacti even. Near Vera

Cruz, where the highway reached the Gulf of Mexico shore, I saw people

on the beach. The route inland again traversed mango orchards, sugar

cane fields, banana plantations, pastures with Brahman cattle and broad

rivers with people swimming and washing clothes. The Gulf coast region

is warm, moist, and green. In Valle Nacional the vegetation is lush

and vibrantly green, young corn and potato plants dot fields, orange

trees are laden with fruit and people are preparing land for crops.

Today I arrived in the true tropics. I'm excited and animated by this

passage through such verdant terrain, by the many kinds and the great

size of trees and by the vivid colors of the trees abloom, white, pinks,

reds and purples. Living trees form many pasture and parcel fence rows.

One entire row was ablossom in dazzling red. It probably hasn't

frosted here in 10,000 years.

This favorable, two crops a year habitat gave rise to Mexico's first

civilization, the hypothesized mother civilization in Middle America,

the Olmec. Until the second half of the nineteenth century the Olmecs

were unknown, a truly lost civilization. In 1862 a colossal stone head

was discovered in Tres Zapotes and subsequently published several times.

At the beginning of this century other Olmec artworks and sites received

study. In 1929 Marshall H. Saville, whose study of Olmec objects began

in 1900, named the culture.

Olmec civilization, and thereby Middle American civilization, began

before 1200 B.C. in the Olmec heartland, the hot, tropical coastal plain

south of the Gulf of Mexico. The Olmec invented sculpturing colossal

bodiless heads, 4' 8" to 9' 10" in diameter. Great monolithic rectangular

solids and stelae up to 17 feet tall were also carved. Stone sculpture

stands as the greatest evidence of Olmec civilization.

Several areas influenced by the Olmec which developed civilizations

with predominantly local traits have been called Olmecoid groups. Monte

Alban in Oaxaca and Izapa in Chiapas are so classified. The Olmec culture

is considered to have been the most influential on a regional basis

though these centers developed in parallel. Tomorrow's travel will be

a steep climb back over the formidable Sierra Madre to visit the Monte

Alban ruins and the city of Oaxaca.

Today life in the tropics has been inexpensive, total spending was

a new low. The hotel in this village costs $1.20 as did dinner with

two beers. In La Tinaja I paid 87¢ for a typical roadside lunch,

four pork fat tacos, two beef cheek tacos and a soda.

Jan. 12. 6 a.m. Valle Nacional could well be the rooster capital

of Mexico. There's a non-stop crowing contest in progress.

7:36. The roosters have given way to the many local songbirds,

radios and jukeboxes. It's Sunday morning and subsequently there is

very little traffic in this remote village.

9:11. After finding a good breakfast I began walking. On the

bridge near the edge of town I met a Chinantec Indian couple. We walked

together discussing aboriginal medical knowledge, for which the Chinantecs

are noted. They informed that many people know treatments and practices

utilizing local plants. When we passed blooming morning glory plants

they said they think some people use them pharmacologically. The ground

is wet so I asked about rainfall. "It hasn't rained for a month," the

man reported. Here near the valley floor it must dew daily. At the first

curve past the bridge an ascent began. When we arrived at the end of

a long grade I stopped to rest and said good-byes.

10:30. Another cardiopulmonary rest. Wow, what an incredible,

steep roadway this is; I've arrived at a 10 degree grade of S curves

on a near vertical cliff, now many meanders above Valle. The fourth

car to pass today now approaches.

Too full and in first gear. All the people walking, Chinantec Indians,

stop and briefly chat. It seems to be a local custom. I invited a man

carrying a heavy load of empty soda bottles with a forehead strap

to test my hip-loading backpack. He agreed that it's more comfortable

to bear, though heavier than his load. I hear another vehicle.

Too full also, not to mention that few vehicles have brakes and clutches

capable of stopping right here. Onward. Upward also on the steepest

of mountains to beyond 9,000 f.a.s.l.

10:53. A photo stop and a necessary rest. Another vehicle sounds

in the distance, straining upmountain.

4:39. Sitting beside the toad stela amidst the Monte Alban ruins.

I caught that ride. My kind driver, Ruben, is here also. We arrived

at 3:00 and have enjoyed various vistas. It is a bright, hot cloudless

afternoon. A cooling wind blows across this mountaintop.

The hitch from Valle Nacional was quite perfect. The winding, steep

climb up the Sierra Madre features a continuous vegetation transition

from hot, tropical rain forest all the way into cool pines. The descent

is through a dry shadow semi-desert ecology. We crested the pass just

after noon and stopped to watch clouds roll over the ridge and disappear

into the drier interior air mass. After gathering Indian Paintbrush

blossoms we continued. At the first switchback a hawk plunged into our

field of vision in a fast, full dive into the roadside vegetation, landing

a car's length in front of us. Wow! I turned and watched it take flight

with empty claws. Beyond Ixtlan we stopped again, to collect bromelaids.

I'm enjoying the good fortune of a ride with Ruben, who, besides being

intent on enjoying a leisurely Sunday, is also going to my other destination.

Later we will drive to Oaxaca City, visible in the valley 1300' below.

There I wish to find one of 250,000 inhabitants, though all I know is

his P.O. Box number.

This mountaintop, a geologic island where three valleys meet, was the

greatest of all Zapotec sites. Construction, which began about 2,500

years ago, preceded the founding of Teotihuacan. Between 500 and 1,000

A.D. the 40 square kilometer city saw the greatest amount of building,

including most of the excavated ruins we view today. Abandonment occurred

towards the end of the 10th century. Thereafter the mountain became

a great necropolis. The most ornate and splendid tombs and the most

significant treasure so far discovered in America have been unearthed

here.

One of the earliest structures, dating to the 5th century B.C., includes

a great wall with monolithic slabs carved in bas-relief with Olmecoid

life-sized human figures, glyphs and numerical signs. These "Dancers,"

so called because they present unusual postures, and their glyphs provide

the earliest proof of writing and a calendar in America.

In the course of 1,5000 years human hands transformed the natural shape

of the mountaintop into a complex geometric form of platform mounds

surmounted by pyramids and thick walled buildings surrounding a central

650' by 1000' plaza. Some of the platform mounds contain natural rock

cores. We are seated facing the Great Plaza with our backs to the Ball

Court. A large building-crowned pyramidal platform mound dominates the

center of the plaza. South of it stands Building J, a unique arrow-shaped

construct. Oriented differently than the other buildings, Building J

is thought to be astronomically aligned. We are about to examine Building

J and climb the tall pyramid-crowned platform south of the plaza.

Jan. 13. Just after midnight. Ruben and I left the ruins at

6, closing time. He said he was going near the city center. He turned

off a block before the zocalo. I jumped ship with a "Thank you friend,

it's been a great day traveling together." I walked to the zocalo corner,

got my bearings and then inquired about a room at the always full Hotel

Plaza. It was full as expected. I returned the half block to the arcade

of the zocalo plaza for the public phone, thinking Dan might have a listed

number. Once there I saw that there were no phone books. I turned and

to my surprise Dan was walking towards me with an immense grin.

We had an enjoyable evening discussing coincidence, the future, writing

and our mutual interests. Our morning plan is to explore a local museum.

1:00 p.m. Museo Frissell. Mitla, a small town east of Oaxaca

with a beautiful, large ruin as well as a superb museum of ancient art.

I was drawn to this museum by published reports of mushroom-shaped carved

stones of various sizes. Again I've enjoyed spending time with someone

I know. Dan will return to Oaxaca while I hitch toward Chiapas. The

next museum awaits in Tuxtla Gutierrez, the capital of Chiapas state.

After Chiapas the next country, Guatemala, awaits. Many countries lie

between here and other friends in Perú.

4:04. A late lunch. I caught a ride atop a load of brick with

two other riders. Flying ceramic particles are an ocular nuisance. The

riders immediately asked if I was interested in mota, claiming their

village produces the very best available. They export by the planeload

and once a plane failing to lift off and crashed, yet both pilot and

mota were saved. After this brief promo they asked if I wanted to take

a crop north. I inquired about antiquities and their linguistic heritage.

Though their village is surrounded by Zapotec Indians they speaks only

Spanish. They claim their village was settled by refugees of the revolution,

they know not of antiquities and they claim to have a few green-eyed

people. I believe it.

Between their turnoff and this restaurant a group of school teachers

painting "Support the teacher's strike" on a roadside rock facet hadn't

thought ahead far enough to fit all the letters. Perhaps the students

should go on strike.

10:34. Hotel Donaji, Tehuantepec. During the several kilometers

I walked after leaving the restaurant I noticed someone following me.

I was curious so I stopped a while, allowing my obvious tail to catch

up. He asked where I was from. I responded with the same question. He

said he was from Mitla. He asked if I was interested in any mota, asking

how much I paid per kilo. This young character, perhaps 18 years old,

was certainly taking a quick, direct approach.

"Do you have any?" I asked disbelievingly.

He said, "Yes."

"Let's see it," I said.

He explained that we need only turn down the next side trail.

"Forget it," I responded.

He began grabbing and feeling my tent roll and sleeping bag and asked

what I was carrying. Still walking, I responded, "Books, papers, clothing,

my house and bed." He didn't relate.

He asked me to give him my sunglasses "to show that we are friends."

I refused. "I know you're a smuggler," he said, adding that he could

call the police so they could inspect my pack or I could give him my

sunglasses and we would be friends.

I urged him to call the cops because, "they should get to know you

better." Again he asserted that he knew I was a "marijuanero" and asked

if I was armed.

"Do you think I would be walking down this road unarmed?" I retorted.

I felt it was time to get rid of the jerk. As a car approached I asked

him to bug off so I'd have a better chance of obtaining a lift. He moved

to block my being noticed and again asked what I carried. I said I wanted

him to go away. He asked why and I answered, "Because it's what I want."

Another car passed.

"Are you afraid?" he asked. I told him in no uncertain terms to leave

my vicinity.

"Do I have to shoot you to see what you have there?" he asked.

I firmly restated what he would do immediately, leave. He walked the

trail over the riverbank edge about 100 ft. away, then threw a rock

at me. I stared down the second rock, which barely missed, then pulled

out my shirttails and moved my hand to my pants top. He quickly ducked

below the bank and I saw no more of him.

Again I rode in the back of a truck, this time with five men and one

drunk. When offered a cigarette I said, "I don't smoke."

"Not even the good stuff?" one man asked. Obviously, they grow marijuana

in the Oaxacan mountains.

Immediately after they detoured I caught my first bus hitch, a full

bus with seventy passengers and standing room only. We lost an hour

en route fixing a flat. I enjoyed helping out in good hitchhiker tradition.

Passengers formed a circle of entertainment around the operation, telling

jokes and giving instructions. Bus tires are heavy, my hands are dirty.

Jan. 14. 8:06. Breakfast. Tehuantepec. I strolled the central

market building, viewing the flower and plant displays and mountains

of foodstuffs. The fresh fruit is beautiful. The quantity of flies is

repulsive. There are cut pieces of fresh cheese, masa, lots of meats

and even a pig's head, each with its share of flies.

Tehuantepec is ethnically unique. The Tehuana women wear colorful full

length skirts and richly embroidered huipils. The women operate businesses

and conduct most of the marketing. Such is local tradition. Tehuantepec

is also the name of this isthmus, the narrow section of lowland which

separates North America and geographic Central America. Powerful wind

currents blast this region for months each winter, blowing from the

Gulf of Mexico towards the Pacific. Near here I once saw a truck blown

over beside the road. No uncommon, I'm told.

Jan. 15. 8:34 a.m. Tuxtla de Gutierrez. I went to bed to the

sound of fireworks at 12:30. I awakened to fireworks at 5. Beyond a

doubt the early morning blasts awakened the roosters also, and they

continued crowing thereafter. Even in the center of this large city

there are roosters. I arose early and strolled the pedestrian mall between

the Regional Museum, the Orchid Garden, the Botanical Garden, the Children's

Park and the State Theater, a commons decorated with carefully tended

flower planters and busts of the revolutionary heroes. While there more

fireworks rang out so I asked a young man why. He responded that it's

the feast of some Virgin. That's all he knew.

I am enjoying breakfast at Jugos Mazatlan. One can choose smoothies

made from any or any combination of the following ingredients: orange,

carrot, papaya, melon, apple, guanabana, watermelon, pineapple, banana,

mango, oats, guayaba, strawberry, tascalate, peach, alfalfa or lemon.

A strawberry smoothie with four avocado and chicken tacos costs $1.

The museum opens soon. I'm off to see a few more archaeological treasures,

another morsel of our vast human heritage.

9:24. Regional Museum of Chiapas, the Anthropology Salon. One

of the charts illustrates the oldest human occupation sites known in

the Americas. To list a few of the oldest: American Falls, Idaho, over

40,000 years; Santa Rosa, California, over 37,000 years; El Cedral,

San Luis Potosí, about 33,000 years; Old Crow, Yukon, about 29,000 years;

Meadowcroft, Pennsylvania, 19,610 + 2,400 years. Listed are 18 sites

exceeding 11,000 years, 8 North American and 10 South American. Another

drawing displays distribution of the very old Clovis points, showing

two concentrations, Sonora, Mexico and highland Guatemala. In Chiapas

a culture called Ocos occurred 3,000 to 3,500 years B.P. in 20 known

sites. Their fired clay objects include facial busts, figurines, sculptures

and containers of various colors and designs. Stratified society is

thought to have originated 3,000 years ago due to agriculture and excess

production. Olmec cultural influence began between 3,000 and 4,000 years

ago. Solid clay Olmec type figures appeared 2,800 years ago. Teotihuacan

influence, both cultural and commercial, followed. Obsidian and silex

and other raw materials were imported from central Mexico.

10:50. In the History Salon admiring a beautific 18th century

oil painting of a shepherd kneeling in prayer before a tree entwined

with heavenly blue morning glory blossoms. White lilies, transparent

white morning glories and other flowers bloom near the shepherd. Birds

fill the air. One of two angels standing behind the shepherd points

across canvass to the tree. This immense image painting by an anonymous

artist bears a dedication to a Chiapas bishop and the following Latin

inscription: "Prote caclicolae pavare gregemifatur en it. Opilio, vt

pascant te quoque tempus erit." That's more Latin than I can translate.

12:07. The museum restaurant. Prices are tourist based so I'm

enjoying local coffee only. The decor is a carefully planned modern

artistic expression with black and white clowns, fans, accessories and

the marble floor. The plants and immense Palenque ruin photos are green.

This impressive museum building was constructed in 1982.

I've photographed some unique modern art in the History Salon as well

as the 18th century painting with botanicals. I want to take archaeology

photos next. Then I will inquire about the mushroom stones this museum

possesses. They were not on display as expected.

The waiter arrived with change, charging an extra 25¢ U.S. for

creamer. Imagine the world's most expensive cup of coffee here! I couldn't

so I argued. The rest of my pesos just arrived. Nice try fella!

12:31. Waiting in the museum offices for permission to use a

tripod in the archaeology gallery. The guard didn't allow me 10 ft.

past the salon door upon seeing my equipment. Now I'm told, "Yes, it

is permitted."

1:26. In the inner sanctum, the "hands on" section, the archaeology

workshop. I just photographed several mushroom shaped pottery forms

which seem to be utilitarian items, their rounded tops are well worn

from use. The mushroom shaped stones are being brought out of storage.

2:35. Having lunch. An inquiry about the beautific oil painting

led to the office of A.R., a museum historian. We walked to the History

salon. While standing before the painting we discussed the ethnobotanical

details. Though A.R. did not find additional data about the painting

she promised I could expect further information in the mail. I'm curious

about the painter's identity and other available historic details. We

discovered we have a mutual acquaintance. Now onward to San Cristobal

de las Casas, high in the Central Chiapas mountains.

10:54 p.m. I arrived after dark. I'm in a $1.75 room in some

sort of hospedaje. The place is unlabeled. There are lots of illegal

Central American refugees in this area, and I didn't ask questions.

The clerk at a full hotel sent me to an intersection where I was met

by the man who led me here. The price is right.

The first ride from Tuxtla was with a topaz miner who spoke about insects

and organic material found in rare topazes. It is hypothesized that

prehistoric genetic material may be recoverable from such sources in

the future. At the Chiapa de Corzo junction the first car to pass picked

me up. The driver, a man of Cuban-Spanish descent, advised me to be

very careful in Nicaragua because "they don't like Yankees." As I near

Central America people are warning of dangers.

From Chiapa de Corzo the highway ascends. The view of the valley and

pyramid ruins from the steep mountainside was stupendous. At the Villa

Hermosa junction, where the panorama is also precious, I began walking

without hitchhiking, climbing higher and higher, enjoying the slow pace

at which the view changed and hoping to attain an even loftier view

of the valley. When the road leveled and the view diminished the first

people I thumbed, a young Swiss couple driving an American camper van,

stopped. A lively conversation followed about travels, tourist sites,

and interests. We made photography stops during sunset. One of them

took a photo of a Native child in beautiful, bright-red hand-woven garments

and in return got pelted with a pebble. There are Indian groups with

beliefs that metal objects pointing at them can take their spirits away.

I think this problem originated with firearms. Sunset from high elevations

overviewing fields of clouds featured a spectacular blend of soft, pastel

tones. The route from Chiapa de Corzo is an enchanting part of the world.

Colonial churches tower above the tile roof towns. The cornfields are

very productive. The largely Indian population wears authentic native

garments, hand woven and brilliantly colorful. And the geography is

lofty and breathtaking.

Upon arriving we parked near the zócalo and immediately met two Swiss

who they had met elsewhere. They led us to a small restaurant popular

with local foreigners. A party developed as musical instruments were

brought out, tables were pulled together, rounds of beer were consumed

and information about sites, ruins, towns, and plans was exchanged.

I really enjoyed the gathering.

Jan. 16. 10:24 a.m. Santo Domingo church. Surrounded by altars,

a multitude of burning candles, scrollwork and chanting natives. I wish

I had a tape recorder. The chanting is mesmerizing, very musical, truly

harmonic. The only words I recognize are "Jesu Christo." The singing

is in native language. Here in the side vestibule the chanters kneel

before their low floor altars facing the vestibule altars. Two separate

groups of people are present, each with one or two singers plus someone

lighting the many floor altar candles. Their children's voices also

fill the air. Their faces are brightened by candlelight and prayers.

Vases of fresh flowers decorate the altars with colors that match the

native clothing. Sculptured flowers, leaves and grape bunches grace

the scrollwork. On a sculpted cross a design similar to Mayan water

lily depiction replaces the usual grape leaves.

A narrow shaft of light entering via a small octagonal window in the

central dome makes apparent the candle smoke and the movement of the

earth. The gold colored scrollwork filling this temple seems bright

though the lighting is low. I am now near the side entrance and a much

adored painting of the Blessed Virgin Mary with prehispanic designs

overlaid on the skirt. Before it are candles and a vase with cedar branches

and flowers, the only non-altar to receive such treatment. Passing people

sign the cross, some genuflect and others even kiss the woodwork. I

set up camera, cable release and tripod and took a multi-second exposure

of the canvas. While the lens was open a worshipper reached up into

the frame and touched the design after kissing his hand.

The chanting has continued non-stop for nearly an hour. It's 11:01.

On to the New World Archaeologic Foundation. Their library is one reason

I'm in this former colonial capital.

2:06. Having lunch. In the NWAF Library I found the data I sought.

They excavated Izapa and many other Chiapas ruins. G.W. gifted me a

copy of the album of Izapan sculpture, a NWAF publication.

7:12. La Trinitaría. Nighttime began as I stood beside the road.

It seems that traffic is nil beyond La Trinitaría after dark. I found

this restaurant but no hotel.

The rides this afternoon were in the backs of vehicles with a total

view of the surroundings. South from San Cristobal has been a transition

to poorer and poorer land and consequently poorer corn, poorer people

and humbler dwellings. On this high plateau the wind blows forcefully.

Low clouds move swiftly overhead towards the Pacific only to disappear

into the drier air mass. A multitude of clouds pass, yet the cloud front

does not advance. Sunset was pastel.

I wonder if the tall mountains to the south are in Guatemala. Yes,

they are. A local teacher dining at a neighboring table also reports

that this is not an ethnic area, the population is recent--not surprising

in view of the poor local ecology. Now to find a place to crash. Often

the easiest solution is to ask the local police. Several are dining

at an adjoining table. That was easy. Tonight it will be sweet dreams

at the local cop shop, the "Comandancía."

8:07. This isn't exactly the Comandancía, it's the sidewalk

out front under the veranda. The plaza verandas are a common camping

choice in this part of the world. I recall arriving in Ocosingo, Chiapas,

the day before an important fiesta and finding the verandas as filled

as the hotels.

Jan. 17. One month on the road! Breakfast. Comedor Mechita,

Paso Hondo. Sleeping on the sidewalk is a lesson in how much sleep one

really needs. In a soft comfortable bed it's possible to sleep at almost

any time and, most certainly, for hours longer. Having walls as a sound

barrier also makes sleeping easy. The roosters began to crow before

first light. I rolled over several times trying to find the position

that had been adequately comfortable while I still needed sleep. At

6 o'clock with faint light through the clouds, roosters crowing and

church bells tolling a half-block away, I arose from my concrete mattress.

With the car I helped push-start at the Pemex station I rode down from

the rocky highlands and out from under the clouds. Trails of fog were

visible in the valley. We passed poor, rock-terraced corn and boulder

fields and quickly arrived in the rich valley bottomlands The driver

offered the opportunity to explore a cave which an old country friend

of his knows about, a cave with prehistoric artifacts, including a green

statue. He said there are ruins near the cave that are unknown to outsiders.

What a tempting offer. This entire region is archaeologically abundant.

Last night on the sidewalk I had a non-stop conversation from two to

ten people for hours and Oscar, who was there for the duration, offered

to bring two stone monkeys from his home.

I detoured at the Tapachula junction, walking and collecting seeds

along the road to Paso Hondo, an assemblage of humble dwellings amidst

beautiful flowers and flowering trees with shades of red and a bright

purple as the prominent colors of the vivid local ornamentals of choice.

The ecology changes quickly in this mountainous region. Cool, rocky

plateaus and lush tropical valleys are only a few miles apart. Yet more

ecological zones lie between here and tonight's destination, Tapachula,

on the Pacific coast piedmont.

Mmmm. What a great breakfast I've found, the best huevos a la Mexicana

to date and exquisitely seasoned beans. Amend that, I just asked what

seasoning in the beans gives such great flavor and was told that the

only additive is salt. The cook claims the flavor is due to the earthenware

beanpot. I stand corrected on the seasoning. The flavor is nonetheless

exquisite, mmmm.

9:41. After a ride from Paso Hondo to Cosalapa I decided to

walk because the roadsides feature so many flowers. Chanting resounds

at this, my second stop to collect seeds. The singing in native language

interspersed with whistling comprises an enrapturing sound. I sit facing

the house from which it emanates. The singer now passes into view through

her open doorway. She is sweeping. Again I wish I had a tape recorder.

12:36. I walked miles then stopped for a sizable blooming orchid

patch nestled where the tall trunk of an immense tree branches into

massive lichen covered limbs. Sunlight filtered in, illuminating that

most pristine and beautiful floral sight of this journey, a perfect

arboreal garden. I caught a ride and then bailed out for a large patch

of unusually colored morning glories beside the road.

After collecting seeds and photographing I loaded my pack just as Salamón,

at whose table I now sit, and his family passed. I inquired about their

name for the morning glories. They responded. "campanñitas," and seemed

to attach little importance to them. We walked together discussing Salamón's

immediate plans to travel to Perú with me. I reached down and plucked

a yellow flower and they said that the blossom is very sweet. Salamón

pointed out an orange flower across the road in case I was interested.

I pointed to an impressive row of giant cactus on their property edge.

Salamón volunteered, "It's a medicine, it reduces fever." We walked

to the cactus, which he called "organo," and with his machete he cut

a chip of bark off a lower trunk, saying it is the medicinal part. The

bark is smooth and spineless and covered in part with a brown peel.

The green, ribbed, spined upper branches resemble a Trichocereus species.

I'm being treated to a soda, a real luxury item among these rural, land

dependent people. They are not drinking any at the same time. I asked

Salamón how the organo bark is prepared for use. He turned to his wife,

Beatrice, and asked, "How is it done?" First it is boiled, then crushed

and then the water only is drunk.

On the wall above them is written, "Woman, you were made from man's

rib, not his head to surpass him, nor his foot to thread on him. Woman,

you were made from his rib to be his equal, from below his arm to be

protected, from beside his heart to be loved." I've asked if they have

a wedding picture. They have no pictures of themselves. I'm about to

do the honor.

2:07. Lunch in Motozintla. More huevos a la Mexicana, this time

with rice. It's a good thing I like eggs, the eateries I'm finding often

have little else except, of course, beans and tortillas. I'm hungry

and thirsty. Again I've walked miles. My legs are tired. The road from

Cosalapa up the Grijalva River valley has led to progressively higher

and drier terrain. The organo cactus is the dominant plant of the landscape

near Motozintla.

6:51. Hotel Cinco de Mayo, Tapachula, after a cold shower. I

forgot to ask about hot water and didn't note the single shower valve

while inspecting the room. I avoid cold showers when possible.

From Motozintla I rode atop a truck, immediately ascending the mountainside

into pine woods with a few small cornfields and an occasional view of

the village filling the very steep valley wall to wall. In one forest

area long, draping lichens and a strong pine scent filled the clean,

fresh air. At the pass the windy divide is green with short grasses.

The transitions continued with a direct descent to the coastal plain,

a steep, continuous downgrade in a narrow valley through forests, pine,

deciduous, subtropical and tropical. Here at 500 f.a.s.l. on the Pacific

Coast plain it's really hot. A hallmark today was many butterflies.

Also, I got sunburned.

Jan. 18. The Izapa ruins, a site occupied beginning approximately

3,500 years ago, a millenium before Monte Alban. Archaeologically this

hot and fertile region is noted for Izapa's highly distinctive style

of bas-relief stone sculpture on the largest pre-Maya assemblage of

carved stelae. The monuments were carved from 300 B.C. to A.D. 250.

Izapan art is significant because it represents an early stage of Mayan

iconography. The meanings of the symbols are not entirely understood.

I'm sitting in the shade in the southwest corner of Plaza B, facing

mountains to the east. Within this grassy, park like clearing stand

a large grass covered pyramid, a variety of elaborately carved stelae,

three stone spheres atop cylindrical stone pedestals and a few trees.

The standing stones align to the eastern horizon positions of the following

events; moon maximum and minimum north and south, Venus maximum north

and south, summer and winter solstice sunrise, equinox sunrise and solar

zenith sunrise.

The 6 foot tall stela beside me, Stela 12, is the backsight for both

the summer solstice and zenith passage sunrises. It also serves as a

fence corner post. Barbed wire wraps around the unsculpted backside.

This vast, complex pyramid site is today inhabited and cultivated. Three

park like plazas, literally pastures, contain almost all the sculpted

stelae and several of the many pyramids. Thatch-roofed dwellings are

everywhere between and on the pyramids. Pigs, turkeys and chickens graze

and forage the plantation covered ruins. The site literally is being

shat upon by a variety of domestic animals and seems productive. This

corner post stelae is deeply shaded by cacao trees, so much so that

lichens grow on the stone. Though the images are difficult to discern

the relief carving is obviously a great work of art.

1:43 p.m. Plaza A. Astride a giant stone toad, more precisely

on the left paratoid gland of Altar 2. The toad image is several times

repeated. Prominently featured are their paratoid glands which elaborate

and secrete numerous chemicals bioactive in many metabolic pathways

in humans and other animals. What importance did toads have to Izapa's

prehistoric inhabitants? A source of medicine? The answer remains a

mystery.

Upon departing Plaza B children solicited my signature in a tattered

register book. I inquired about other stelae and thereby was led by

a young girl through a banana plantation to the largest of the sculptures,

Monument 2. The immense stone head emerging from the earth has a larger

than life human form in its wide open maws. The human image is incompletely

represented, roughly shaped and simple. The timeworn, eroded monolith

lacks perfect symmetry and has an ancient, even archaic, character.

The sculptures have thatch roofs of the simplest sort which are fast

becoming downfallen. Thatch debris litters the carvings. "Why the roofs?"

I asked. The young girl answered that they prevent breaking of the stones

by lightning. That seems a most unlikely reason. The roof above this

toad is providing ample and welcome shade.

My information indicates that there are 87 stelae, including 28 with

carvings. The carved stelae are about 6 ft. tall and up to that wide,

are slab like and typically present imagery on only one surface. Many

of the carved stelae have before them low, plain or decorated stone

platforms which archaeologists have named altars and thrones. I'm not

sure how to distinguish the altars from the thrones and, besides, they

seem intended as seats from which to contemplate the carvings. My seat,

the toad, is positioned before a sculpted stela.

This plaza, Plaza A, has stelae and pyramids on all four sides. The

pyramids are unexcavated, overgrown and outside the fenced grassy enclosure.

The plaza is the neighborhood soccer field, for which it is not quite

large enough.

Along the pyramid base on the northern plaza edge six sculptured stelae

once stood. Several have been moved to museums. The central and forward

most of those remaining, Stela 6, depicts a fantastic creature, part

toad, with paratoid glands. It has five digit hands and feet, has very

long fingernails, sits upright, is rotund and faces upward. The creatures

mouth is open and its bifurcated tongue reaches up to touch a "U" glyph.

Beside me, on Stela 3, a human head in a "U" glyph floats above the

open jaws of a double-tongued snake-like being. Beside them stands a

masked human figure. Nearby Stela 2 depicts an immense winged person

floating upside down above two people and one of the earliest Mesoamerican

Tree of Life figures. The prehistoric local artists imagined intriguing,

fanciful scenes, the meanings of which remain a mystery.

2:22. Plaza B again. I inquired with the gatekeeper's family

about purchasing drinks in the neighborhood. They are bringing down

a coconut from the closest palm. In the cooking shack a woman is palming

tortillas on a metate. A young boy just handed me the opened coconut.

What a treat, for its hot and humid. I'm sweating. A slight breeze is

blowing. From within the hut a commanding woman calls for chili peppers.

A full 10¢ coconut is a lot of juice, even on a hot, thirsty afternoon.

2:53. Back at the corner post stela, enjoying the shade and

waiting the earth's turning for a change in lighting angle. Time permits

cleaning dirt and lichens off the seat. This shaded corner is little

visited and needs work.

3:37. Atop the large pyramid. There are several hearth spots

indicating present day use of the pyramid by humans. Also cows graze

the plaza and pyramid so one must step with care.

4:55. Tapachula. Cinco de Mayo market, awaiting duck soup in

a comedor without a name. One of the two women, referring to her coworker,

said to call it, "the comedor with the beautiful girl." I asked the

women what they were whispering and the same woman reported that the

beautiful girl wants to go with me to the USA. I said I'm going to Perú.

They answered that sounds fine, that she'd go.

I can't find any meat in my soup, but there's lots of fat and some

real big bones. I began to wonder what sort of animal I'm eating so

I held up a large, long fatty cylinder-shaped thing and asked the cook

which part of the duck it is. They say it's the tendon and all this

seems funny to them. Damn, I got served Hoof of Beef soup, not duck

soup. In Spanish the difference is one letter; pata v. pato, which is

also the difference between a female and a male duck. My mistake. Being

entirely unaware of hoof soup led me to assume they offered female duck

soup, "sopa de pata." "Hoof soup is very popular, very Mexican," the

women assure me. Take my word for it, its no cup of tea. It's quite

tasteless. I'm consuming the broth only, not the tendon and cartilage

chunks. The laugh's on me.

9:57. A hot, humid night though the dormant ceiling fan belies

hotter seasons. My stomach is feeling normal again. There was something

unsettling about mixing coconut juice and hoof soup.

There is a hole in the ceiling, a necessary ventilator shaft of sorts.

I've been conscious of it because people walk about on the roof. The

management dwells up there and I can see linen on the laundry lines.

I looked up a moment ago just as someone stuck their head into the shaft.

Given the architectural details, I suppose it's happened before. Cheap

trills in a cheap hotel. What next?

Jan. 19. 9:29 a.m. The Tapachula Museum. The doors opened at

8. So far I'm the only visitor. Two brothers, ages 10 and 18, are taking

care of the place. Minutes ago three policeman arrived. There's no gold

or jade to guard though there is plenty to see. I've kept busy viewing

and photographing. The young caretakers assisted in changing lighting

and moving statues and plants as needed. Unluckily seven of fifteen

display cases have burnt out lights. They say it will be fixed soon,

but first the bulbs must arrive from Tuxtla.

Several Izapa stelae are displayed here, as are many other pieces excavated

from the ruins. There are mushroom shaped stones and other beautiful

small stone sculptures, mostly anthropomorphic figures. One small, simple

stone head has a face inscribed in its mouth. A face or a person in

the mouth of an animal, often a snake, is a common prehistoric motif

in Middle America, especially in Mayan art.

Several display cases have fired earthenware figures with a noteworthy

feature in common, facial expressions. Explicit emotional states are

depicted with the plastic clay medium. One figure appears ecstatic.

Another odd facial expression, suggestive of teeth gritting, is rather

disconcerting. Others stick out their tongues. Some figures are goggle-eyed

and fanged. Many have ear plugs with a variety of adornments, including

flowers, animals, and geometric forms. One figure has a snake projecting

from one ear plug and a fish from the other. Did these details convey

meaning?

The museum building is 12 sided and about 64' across. In the center

is constructed a thatch-roofed shack surrounded by a circular planter

of river stones. Snake plants, dumb canes and stone sculptures surround

this typical huts outer walls. The floor is earthen. I'm seated

on a simple wooden bench and writing on a folding card and checkers

table. This is a real home-grown museum, quaint and comfortable.

12:48. La Parrilla Restaurant. Near the central Plaza and a

block from where the museum will soon relocate. I stopped writing the

museum description when the director, Antonio, arrived. We conversed

and exchanged ideas and information until noon. Antonio is interested

in the astronomic orientations of the Izapa pyramids and stelae. He

lacks exact enough data to set up a new display. The data is available

in English in the USA. Antonio reported that on the night of full moon

a group of people gather on the pyramids and claim to feel forces present

there and to achieve out-of-the-body experiences. Perhaps they made

the campfire hearths I saw. Doing out-of-the-body experiences there

would be convenient considering the grazing evidence littered about.

I hope I don't damage my only shoes while doing night photography

later.

In the restaurant I count 13 staff and one other customer. Let me amend

that, the other customer is the boss. The waitress just gave her my

$20 traveler's check. She is going to the back for change.

3:33. On the toad again. Five cattle staked nearby are busily

manicuring the soccer field, a sound far superior to that of a modern

lawn mower. In the distance I hear a truck going through the gears.

Birds of differing voices and insect sounds truly fill the air. A rooster

crows and the afternoon breeze rustles leaves above. It's a hot January

day. I'm enjoying the shade. It's partly cloudy overhead and appears

entirely cloudy around the volcanoes to the east. I hope the afternoon

will have some cool moments. The sun is intense. Oh! the trails, trials

and toils of exploring tropical lands. While at the museum I examined

a good map of the archaeologic zone for the locations of more carved

stones. Some are nearby and some are near the river. One is in the river,

whereupon I wish to sit and cool my feet.

5:36. Plaza A, Stela 5. While cooling off in the river near

the petroglyphed rock I noticed morning glories all around. They had

evaded my notice for some moments because all the blossoms were closed.

Is that why they are called morning glories? The path to the river crosses

banana, coffee, and cacao plantations and recurring jungle interspersed

with pyramids.

Ants were climbing my legs so I've moved completely onto this 4 ft.

wide stone platform, a convenient seat for studying super-narrative

Stela 5, so-called because it presents more figures than any of several

others combined. It is also the largest stela. Centuries, or rather,

millennia of wear obscures some details. In the bright, diffused light

of day the worn images are difficult to photograph. Night photography

with illumination limited to extreme side lighting achieves contrast

not possible in daylight. The camera is set up with tripod and cable

release. I'm awaiting darkness.

5:51. A young man, the son of the caretaker, was here to ask

me to depart because the ruins are closing. To forestall my expulsion

I gave him an official looking piece of paper, the permission I purchased

allowing me to use a tripod at Teotihuacan. It bears an ink stamp and

letterhead of his father's employer, the National Institute of History

and Anthropology. He departed with the paper.

The sunset is soft pastel toned. Crickets are singing as are the evangelical